Section 2: Implementing a High-Quality Curriculum

The Rhode Island Early Learning and Development Standards

The 2023 Rhode Island Early Learning and Development Standards (RIELDS) are designed to provide guidance to families, teachers, and administrators on what children should know and be able to do as they enter kindergarten. They are intended to be inclusive and developmentally appropriate for all children – multilingual learners, children with special health care needs, children that are differently-abled, and children who are typically developing – recognizing that all children may meet age-level expectations as indicated in the RIELDS.

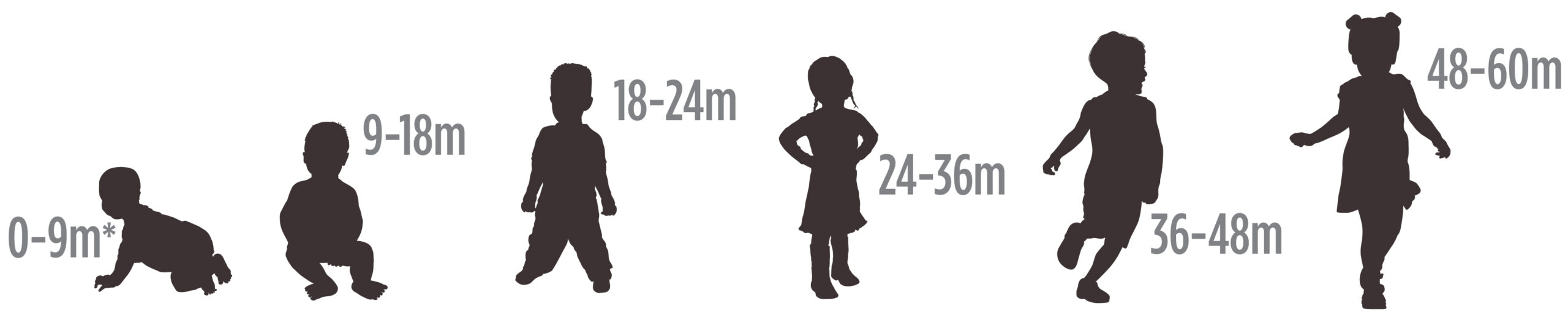

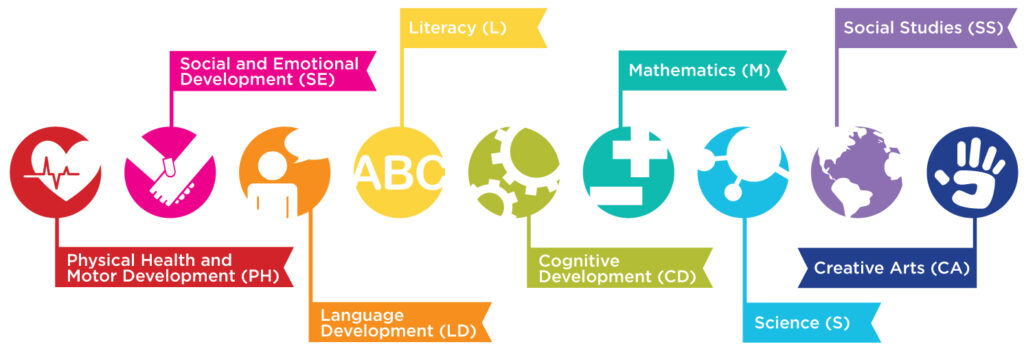

The RIELDS articulate shared expectations for young children’s development across 9 distinct domains: Physical and Motor, Social and Emotional, Language, Literacy, Cognitive, Mathematics, Science, Social Studies, and Creative Arts development. Further, they provide a common language for measuring progress toward achieving specific learning goals (Kendall 2003; Kagan & Scott-Little, 2004). The RIELDS extend educational expectations to infants and toddlers, and they are integrated with preschool early learning standards to create a seamless birth to 60-month continuum and are aligned with K-12 Rhode Island Core Standards for Mathematics, ELA/Literacy, and Social Studies, the Next Generation Science Standards, and the Head Start Child Development and Early Learning Frameworks. The standards are to be used for the purposes of:

While the RIELDS represent expectations for all children, each child will reach the standard milestones at their own pace and in their own way. Therefore, to meet the RIELDS, individual children will require different types and intensities of support across domains. The RIELDS are therefore not intended to be used as specific teaching practices or materials, as a checklist of competencies, nor as a stand-alone curriculum or program: rather, the standards are intended to represent the expectations for children’s learning and development and are to serve as a guide for selecting curriculum and assessment tools.

Organization of the RIELDS

Rhode Island’s Early Learning and Development Standards are organized into domains, components, Standards, and Examples:

Domains represent the broad areas of early learning.

Physical Health and Motor Development

Social and Emotional Development

Language Development

Literacy Development

Cognitive Development

Mathematics Development

Science Development

Social Studies Development

Creative Arts Development

Components are specific areas within a domain.

Domain: Physical Health and Motor Development

Component 1: Health and Safety Practices

Component 2: Gross Motor Development

Component 3: Fine Motor Development

Standards are general categories of competencies, behaviors, knowledge, and skills that children develop in increasing degrees and with increasing sophistication as they grow.

Domain: Physical Health and Motor Development

Component: Gross Motor Development

Standard: Children develop large muscle control, strength, and coordination.

Standard: Children develop traveling skills.

Examples establish the specific developmental benchmarks for the competencies, behaviors, knowledge, and skills that most children possess or exhibit at a particular age for each learning goal. Seen altogether, the examples depict the progression of development over time ranging from Birth through 60 months.

Domain: Physical Health and Motor Development

Component: Gross Motor Development

Standard: Children develop large muscle control, strength, and coordination.

Standard: Children develop traveling skills.

Example (9 months): Children express discomfort or anxiety in stressful situations.

Example (60 months): Children follow safety rules.

Developmental Domains

As noted above, the RIELDS are organized across 9 central domains, by which expectations for children’s growth and development are indicated.

Below is a summary of each developmental domain found in the RIELDS.

Physical Health and Motor Development

The emphasis in this domain is on physical health and motor development as an integral part of children’s overall well-being. The healthy development of young children is directly related to practicing healthy behaviors, strengthening large and small muscles, and developing strength and coordination. As their gross and fine motor skills develop, children experience new opportunities to explore and investigate the world around them. Conversely, physical health challenges can impede a child’s development and are associated with poor child outcomes. As such, physical development is critical for development and learning in all other domains. The components within this domain address health and safety practices, gross motor development, and fine motor development.

Children with physical challenges may demonstrate alternate ways of meeting gross and fine motor goals; for example, by pedaling an adaptive tricycle, navigating a wheelchair, or feeding themselves with a specialized spoon. Children that are differently abled may meet these same goals in a different way, often at a different pace, with a different degree of accomplishment, or in a different order than their peers. When observing how children demonstrate what they know and can do, teachers must consider appropriate adaptations and modifications, as necessary. Principles of universal design for learning (UDL) offer the least restrictive and most inclusive approach to developing environments and curricula that best support the physical health and motor development of all children. It is important to remember that while this domain represents general expectations for physical health and motor development, each child will reach individual standards at their own pace and in their own way.

Social and Emotional Development

Social and emotional development encompasses young children’s evolving capacity to form close and positive adult and peer relationships; to actively explore and act on the environment in the process of learning about the world around them; and express a full range of emotions in socially and culturally appropriate ways. These skills, developed in early childhood, are essential for lifelong learning and positive adaptation. A child’s temperament (traits that are biologically based and that remain consistent over time) plays a significant role in development and should be carefully considered when applying social and emotional standards. Healthy social and emotional development benefits from consistent, positive interactions with educators, parents/primary caregivers, and other familiar adults who appreciate each child’s individual temperament. This appreciation is key to promoting positive self-esteem, confidence, and trust in relationships. The components within this domain address children’s relationships with others—adults and other children—their personal identity and self-confidence, and their ability to regulate their emotions and behavior.

All children, including multilingual learners and children that are differently abled may demonstrate alternate ways of meeting social and emotional goals; for example, children with visual impairments and/or children from other cultures may vary in direct eye contact and demonstrate their interest in and need for human contact in other ways, such as through acute listening and touch. Children that are differently abled may initiate play through use of subtle cues, at a different pace or with a different degree of accomplishment. In general, the presence of a disability may cause a child to demonstrate alternate ways of meeting social and emotional goals. The goals for all children are the same, even though the path and the pace toward realizing the goals may be different. When observing how children respond in relationships, teachers must consider appropriate adaptations and modifications, as necessary. Principles of universal design for learning (UDL) offer the least restrictive and most inclusive approach to developing environments and curricula that best support the social and emotional development as well as the cultural and experiential backgrounds of all children.

It is important to remember that healthy social/emotional development goes hand in hand with cross-domain learning and development. Children’s development of a self-awareness and affirmation, for example, is strongly linked to their learning in Social Studies (e.g., Self, Family, and Community). Their development of emotional recognition and regulation contributes to their development of cognitive skills (e.g., Attention and Inhibitory Control) and their abilities to persist at learning activities in language, literacy, mathematics, and science. Successful experiences in the content areas also positively contribute to children’s social/emotional development.

Language Development

The development of children’s early language skills is critically important for their future academic success. Language development indicators reflect a child’s ability to understand increasingly complex language (receptive language skills), a child’s increasing proficiency when expressing ideas (expressive language skills), and a child’s growing understanding of and ability to follow appropriate social and conversational rules. The components within this domain address receptive and expressive language, pragmatics, and English language development specific to multilingual learners. As a growing number of children live in households where the primary spoken language is not English, this domain also addresses the language development of multilingual learners. Unlike most of the other progressions in this document, however, specific age ranges do not define the indicators for English language development (or for development in any other language). Multilingual learners are exposed to multiple languages for the first time at different ages. As a result, one child may start the process of developing second-language skills at birth and another child may start at four, making the age thresholds inappropriate. So instead of using age ranges, the RIELDS use research-based stages to outline a child’s progress in sequential English language development. It is important to note that there is no set time for how long it will take a given child to progress through these stages. Progress depends upon the unique characteristics of the child, their exposure to English in the home and other environments, the child’s motivation to learn English, and other factors.

Children that are differently abled may demonstrate alternate ways of meeting the goals of language development. If a child is deaf or hard of hearing, for example, that child may demonstrate progress through gestures, signs, symbols, pictures, augmentative and/or alternative communication devices as well as through spoken words. Children that are differently abled may also demonstrate alternate ways of meeting the same goals, often meeting them at a different pace, with a different degree of accomplishment, and in a different order than their peers. When observing how children demonstrate what they know and can do, the full spectrum of communication options—including the use of American Sign Language and other low- and high-technology augmentative/assistive communication systems—should be considered. However, the goals for all children are the same, even though the path and the pace toward realizing the goals may be different. Principles of universal design for learning (UDL) offer the least restrictive and most inclusive approach to developing environments and curricula that best support the language development of all children. When considering Principles of UDL, consider the variation in social and conversational norms across cultures. Crosstalk and eye-contact, for example may have varying degrees of acceptability in different cultures.

Literacy Development

Development in the domain of literacy serves as a foundation for reading and writing acquisition. The development of early literacy skills is critically important for children’s future academic and personal success. Yet children enter kindergarten varying considerably in these skills; and it is difficult for a child who starts behind to close the gap once they enter school (National Early Literacy Panel, 2008). The components within this domain address phonological awareness, alphabet knowledge, print awareness, text comprehension and interest, and emergent writing. As a growing number of children live in households where the primary spoken language is not English, this domain also addresses the literacy development of multilingual learners. However, specific age thresholds do not define the indicators for literacy development in English, unlike most of the other developmental progressions. Children who become multilingual learners are exposed to English (in this country) for the first time at different ages. As a result, one child may start the process of developing English literacy skills very early in life and another child not until age four, making the age thresholds inappropriate. So instead of using age ranges, the RIELDS use research-based stages to outline a child’s progress in sequential English literacy development. It is important to note that there is no set time for how long it will take a given child to progress through these stages. Progress depends upon the unique characteristics of the child, their exposure to English in the home and other environments, the child’s motivation to learn English, and other factors.

Children that are differently abled may demonstrate alternate ways of meeting the goals of literacy development. For example, a child with a visual impairment will demonstrate a relationship to books and tactile experiences that is significantly different from that of children who can see. As well, children with other special needs and considerations may reach many of these same goals, but at a different pace, in a different way, with a different degree of accomplishment, or in a different order than their peers. However, the goals for all children are the same, even though the path and the pace toward realizing the goals may be different.

Cognitive Development

Development in the domain of cognition involves the processes by which young children grow and change in their abilities to pay attention to and think about the world around them. Infants and young children rely on their senses and relationships with others; exploring objects and materials in different ways and interacting with adults both contribute to children’s cognitive development. Everyday experiences and interactions provide opportunities for young children to learn how to solve problems, differentiate between familiar and unfamiliar people, attend to things they find interesting even when distractions are present, and understand how their actions affect others. Research in child development has highlighted specific aspects of cognitive development that are particularly relevant for success in school and beyond. These aspects fall under a set of cognitive skills called executive function and consist of a child’s working memory, attention and inhibitory control, and cognitive flexibility. Together, these skills function like an “air traffic control system,” helping a child manage and respond to the vast body of the information and experiences they are exposed to daily. The components within this domain address logic and reasoning skills, memory and working memory, attention and inhibitory control, and cognitive flexibility.

Children that are differently abled may demonstrate alternate ways of meeting the goals of cognitive development. For example, a child with a physical disability may require adaptive toys to explore cause-and-effect relationships and a child with a speech impairment may use augmentative and/or alternative communication devices to retell a familiar story or activity. Children that are differently abled may reach many of these same goals, but at a different pace, with a different degree of accomplishment, or in a different order than their peers. However, the goals for all children are the same, even though the path and the pace toward realizing the goals may be different. Principles of universal design for learning (UDL) offer the least restrictive and most inclusive approach to developing environments and curricula that best support the cognitive development of all children.

Mathematics

The development of mathematical knowledge and skills contributes to children’s ability to make sense of the world and to solve mathematical situations they encounter in their everyday lives. Knowledge of basic math concepts and the skill to use math operations to solve mathematical situations are fundamental aspects of school readiness and are predictive of later success in school and in life. The components within this domain address number sense and quantity; number relationships and operations; classification and patterning; measurement, comparison, and ordering; and geometry and spatial sense.

Children that are differently abled may demonstrate alternate ways of meeting the goals of mathematics development. For example, a child who is blind may begin to identify braille numbers and a child with a physical disability may identify numerals through use of an eye gaze. Children that are differently abled may reach many of these same goals, but at a different pace, with a different degree of accomplishment than their peers. However, the goals for all children are the same, even though the path and the pace toward realizing the goals may be different. Principles of universal design for learning (UDL) offer the least restrictive and most inclusive approach to developing en-vironments and curricula that best serve the mathematics development of all children.

Science

From the moment they are born, children share many of the characteristics of young scientists. They are curious and persistent explorers who use their senses to investigate, observe, and make sense of the world around them. As they grow and develop, they become increasingly adept at using the practices that scientists use to learn about the world—including asking questions, planning, and carrying out investigations, collecting and analyzing data, and constructing explanations based on evidence. Like young engineers, they also become increasingly skilled at identifying and addressing problems that arise in their play and designing and testing solutions, especially in their constructive play with objects and materials. The RIELDS science domain includes a standard focused on the science and engineering practices as well as standards that address children’s learning of basic concepts in physical, Earth/space and life science. Children deepen their understanding of these concepts gradually over time and many experiences. Crosscutting concepts, including cause and effect, patterns, and structure and function (e.g., how something is made relates to how it is used) are also incorporated and embedded within each standard. Engaging in the science and engineering practices in the service of building their understanding of science concepts creates many opportunities for children to develop mathematics knowledge and abilities as well as skills in the physical, language, literacy, cognitive, and social-emotional domains including essential, but less readily observable executive function skills such as working memory, attention to tasks, and cognitive flexibility.

All children come to a school or community-based setting with a variety of prior experiences in science can take part in and learn science. In relation to the standards, each child will express their development and learning in different ways, at different times, and at different paces. Children that are differently abled may demonstrate alternate ways of meeting the goals of the science domain. For example, a child with a cognitive delay may require additional hands-on-learning opportunities to generalize science content and a child with an expressive language delay may require pictures or photographs to contribute observations and predictions after classroom-based investigations. Children that are differently abled may reach many of these same goals, but at a different pace, with a different degree of accomplishment, and in a different order than their peers. However, the goals for all children are the same, even though the path and the pace toward realizing the goals may be different. Principles of universal design for learning (UDL) offer the least restrictive and most inclusive approach to developing environments, adopting curricula, and facilitating children’s experiences in ways that best support science learning for all children. It is important to remember that the practices of science incorporate a wide range of skills across the domains of development and learning. For example, the practices include multiple opportunities for children to engage in productive talk and exercise language and literacy skills as they formulate questions, explore and describe observable phenomena, record findings, and discuss their emerging ideas with others. As you plan science experiences it will be important to think broadly about children’s levels of development and learning and consider their day-to-day family, home, and community experiences so that you implement and facilitate science experiences that are meaningful and responsive to children’s lives, interests, cultural and linguistic backgrounds, and leverage their strengths, and support areas for growth in context.

Social Studies

The field of social studies is interdisciplinary, and intertwines concepts relating to government, civics, economics, history, sociology, and geography. Through social studies, children can explore and develop an understanding of their place within and relationship to family, community, environment, and the world. Social studies learning supports children’s emerging understanding of social rules, and their ability to recognize and respect personal and collective responsibilities as necessary components for a fair and just society. By engaging with familiar adults and peers through the course of their everyday lives, children across the birth through five continua are introduced to the different perspectives that they and others share and to life within their community – such as an understanding of principles of community care, supply and demand, occupations, and currency (Civics & Government and Economics). In addition, social studies learning helps children to develop an awareness of the passage of time and diversity (History), and place (Geography). As children learn about their own history, the history of others, and the diversity in the environment in which they live, they place themselves within a broader context of the world around them and can think beyond the walls of their home and early childhood classroom.

Children that are differently abled may demonstrate alternate ways of meeting the goals of social studies development. For example, a child with a physical disability may require environmental modifications, such as a lower cubby or extensions on the sink faucets to follow classroom routines such as putting away a backpack upon arrival and washing hands after a meal. A child with a cognitive delay might need picture cues to recall information about the immediate past. Children that are differently abled may reach many of these same goals but at a different pace, with a different degree of accomplishment, and in a different order than their peers. However, the goals for all children are the same, even though the path and the pace toward realizing the goals may be different. Principles of universal design for learning (UDL) offer the least restrictive and most inclusive approach to developing environments and curricula that best support the social studies development of all children. It is important to remember that as social studies learning experiences and assessments are planned to reflect upon the diversity of the children the classroom and how the components within this domain can be represented in ways that are meaningful to children’s individuality, their family, their homes, and their community as well as the ways in which Social Studies development relates to development in other domains. The development of personal responsibility and group membership, for example, have strong links to Social Emotional Development.

Creative Arts

The arts provide children with a vehicle and organizing framework to express ideas and feelings. Music, movement, drama, and visual arts stimulate children to use words, manipulate tools and media, and solve problems in ways that simultaneously convey meaning and are aesthetically pleasing. As such, participation in the creative arts is an excellent way for young children to learn and use creative skills in other domains. The component within this domain addresses a child’s willingness to experiment with and participate in the creative arts.

Children that are differently abled may demonstrate alternate ways of meeting the goals of creative arts development. Children who are non-verbal, for example, may focus on activities that are rhythmic rather than vocal, and children who are deaf or hard of hearing will be able to respond to music by feeling the vibrations in the air. Children with other special needs and considerations may reach many of these same goals but at a different pace, with a different degree of accomplishment, and in a different order than their peers However, the goals for all children are the same, even though the path and the pace toward realizing the goals may be different. Principles of universal design for learning (UDL) offer the least restrictive and most inclusive approach to developing environments and curricula that best support participation in creative arts for all children.

Selecting High-Quality Curriculum Materials

In March 2021, RIDE issued a Request for Information from publishers of evidence-based, comprehensive, and content/domain-specific curriculum for children ages three to five to align with the RIELDS. The review of the curriculum was executed through a two-tiered process: first, with general alignment with the RIELDS and with evidence-based and theoretical methodology. Curricula in alignment with these sections of the rubric moved forward to the second phase of review where it was assessed for alignment with other metrics of high-quality in the early learning context (e.g., classroom materials, child assessment system, developmentally appropriate practice, usability). The curriculum alignment and endorsement process additionally considered elements of differentiated supports present in the materials submitted (e.g., curriculum supports for multilingual learners, children that are differently abled, younger 3-year-olds, children transitioning to kindergarten). Through submissions received, RIDE has been able to endorse a final list of curricula that is RIDE-approved. The assessment and the final curriculum endorsement are intended to be used for the purpose of selecting curricula for use in childcare centers, family childcare homes, Head Starts, Pre-Kindergarten programs, and other early childhood programs across the state. RI Pre-K programs are required to adopt a curriculum that is RIDE-approved. While this is only compulsory for RI Pre-K programs, it is encouraged that other programs utilize a RIDE-approved curricula to best support children’s learning and development in alignment with the RIELDS.

In March 2021, RIDE issued a Request for Information from publishers of evidence-based, comprehensive, and content/domain-specific curriculum for children ages three to five to align with the RIELDS. The review of the curriculum was executed through a two-tiered process: first, with general alignment with the RIELDS and with evidence-based and theoretical methodology. Curricula in alignment with these sections of the rubric moved forward to the second phase of review where it was assessed for alignment with other metrics of high-quality in the early learning context (e.g., classroom materials, child assessment system, developmentally appropriate practice, usability). The curriculum alignment and endorsement process additionally considered elements of differentiated supports present in the materials submitted (e.g., curriculum supports for multilingual learners, children that are differently abled, younger 3-year-olds, children transitioning to kindergarten). Through submissions received, RIDE has been able to endorse a final list of curricula that is RIDE-approved. The assessment and the final curriculum endorsement are intended to be used for the purpose of selecting curricula for use in childcare centers, family childcare homes, Head Starts, Pre-Kindergarten programs, and other early childhood programs across the state. RI Pre-K programs are required to adopt a curriculum that is RIDE-approved. While this is only compulsory for RI Pre-K programs, it is encouraged that other programs utilize a RIDE-approved curricula to best support children’s learning and development in alignment with the RIELDS.

The Selecting and Implementing a High-quality Curricula In Rhode Island: A Guidance Document: outlines the provisions of RIGL§ 16.22.30-33 with regard to adopting high-quality curriculum and includes a list of approved curricula for Early Learning as of January 2021 (Appendix C). The Early Learning and Development Standards webpage on the RIDE website provides further information on Rhode Island’s Approved List of Pre-Kindergarten Curricula, and opportunities and resources for program leaders, educators, families, and other early learning-invested community members.

At RIDE, we are cognizant of the importance of being a part of the global community and support simultaneous multilingual learning. Many of RIDE’s endorsed curricula are offered in both English and in Spanish. If early learning programs are interested in offering a supplemental foreign language learning curricula and assessment, they must ensure that the supplemental programs selected align with the RIELDS and the instructional and assessment guidance provided in Sections III and IV of this framework.

Additional Resources

Tools to support understanding of the RIELDS and selecting of High-Quality Curriculum

Rhode Island Early Learning and Development Standards (RIELDS)

This standards document includes developmental and learning standards for children ages Birth through 60 months. The standards represent the development of the whole-child with focus on standards across 9 developmental domains: Physical and Motor, Social and Emotional, Language, Literacy, Mathematics, Cognitive, Science, Social Studies, and Creative Arts development.

RIELDS Fun Family Activities Cards & Fun Family Activity Cards Toolkit

These family resources offer information and enjoyable ways to support the development and learning of young children, based on the RIELDS. The toolkit resource provides educators with tips on how to use the Fun Family Activity cards to encourage families in supporting their child’s learning and development.

RIELDS Professional Development Trainings

This webpage lists all of the professional development offerings aligned with the RIELDS that are accepting registration at a given time. RIELDS Professional Development courses are available to all educators that are interested in deepening their knowledge of the RIELDS, the curriculum and planning process, instructional cycle, and implementing a program that is aligned with the standards.

Selecting and Implementing a High-Quality Curriculum in Rhode Island: A Guidance Document

This curriculum selection guidance document outlines the provisioners of RIGL § 16.22.30-33 with regarding adopting high-quality curriculum and includes a list of approved curriculum for K-12 as well as pre-kindergarten (Appendix C).

RI’s Approved List of Pre-Kindergarten Curricula

This approved curriculum list indicates curriculum for children ages 3 to 5 that are aligned with the RIELDS as well as against a department-developed rubric that demonstrate alignment to expectations for high-quality curriculum in the state of Rhode Island. This list is intended to influence the selection of high-quality curriculum materials in child care centers, family child care homes, Head Starts, Pre-Kindergarten programs, and other early childhood programs across the state.

2021 Early Learning and Development Standards Curriculum Alignment: Guidance Document

This guidance document provides information to educational stakeholders in child care centers, family child care homes, Head Starts, Pre-Kindergarten programs, and other early childhood programs across the state, on RIDE’s curriculum alignment and endorsement process.