Section 3: Implementing High-Quality Instruction

Part 1: Introduction and Overview

Part 2: High-Quality Instructional Practices

In order to effectively implement high-quality curriculum materials, as well as ensure that all students have equitable opportunities to learn and prosper, it is essential that educators are familiar with and routinely use instructional practices and methods that are research- and evidenced-based. In developing the K-12 curriculum frameworks, RIDE established five practices that are essential to effective teaching and learning and are common across all disciplines. Part 2 begins by outlining these high-quality instructional practices and then dives deeper into instructional practices that are essential and more specific to early learning educational settings, servicing children ages birth through 5 years. Call-out boxes are embedded throughout this section drawing connections between high-quality instruction in the early learning context with the five high-quality instructional practices identified for all disciplines. While these call-out boxes represent a few of these notable connections, readers may notice other parallels between the high-quality instructional practices and the early learning instructional guidance.

High-Quality Instruction in All Disciplines

Below are five high-quality instructional practices that RIDE has identified as essential to the effective implementation of standards and high-quality curriculum in all content areas. These practices are emphasized across all the curriculum frameworks and are supported by the design of the high-quality curriculum materials. They also strongly align with the instructional framework for multilingual learners, the high-leverage practices (HLPs) for children that are differently abled, and RIDE’s educator evaluation system. Below is a brief description of each practice.

High-Quality Instruction in Early Learning

This section discusses several high-quality instructional practices that RIDE has identified as essential to the effective use of the early learning standards (RIELDS) and implementation of high quality curriculum within the early learning context serving children ages birth through five. These instructional practices are organized within three key areas:

Set the Stage for Learning

Foundational early learning instructional principles that will “set the stage” for supporting children’s development and learning throughout the school year.

Get Ready: Prepare the Environment

Important considerations for setting up the physical classroom environment and schedule in ways that are developmentally appropriate, mindful, and responsive to the needs of the children served.

Facilitating Children’s Learning: Instructional Strategies

Specific instructional strategies that support children’s growth and development of 21st Century Skills, including critical thinking and problem-solving, communication, collaboration, and creativity (“The 4 C’s).

RIDE recognizes and is committed to providing all children with equitable learning opportunities that enable them to achieve their full potential as engaged learners and valued members of society. This framework is informed by the National Association for the Education of Young Children’s (NAEYC) Advancing Equity in Early Childhood Education position statement, and includes considerations related to creating a caring, equitable community of engaged learners; establishing reciprocal relationships with families; and observing, documenting and assessing children’s learning and development, all of which early childhood educators may use in practice to promote an inclusive and equitable space for the state’s youngest learners. Furthermore, the topics addressed in this framework will integrate considerations related to promoting universal design, encompassing the birth through five age spans, and supporting multilingual learners and children that are differently abled throughout.

RIDE recognizes and is committed to providing all children with equitable learning opportunities that enable them to achieve their full potential as engaged learners and valued members of society. This framework is informed by the National Association for the Education of Young Children’s (NAEYC) Advancing Equity in Early Childhood Education position statement, and includes considerations related to creating a caring, equitable community of engaged learners; establishing reciprocal relationships with families; and observing, documenting and assessing children’s learning and development, all of which early childhood educators may use in practice to promote an inclusive and equitable space for the state’s youngest learners. Furthermore, the topics addressed in this framework will integrate considerations related to promoting universal design, encompassing the birth through five age spans, and supporting multilingual learners and children that are differently abled throughout.

Set the Stage for Learning

Developmentally Appropriate Practice

The National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC), defines Developmentally Appropriate Practice (DAP) as:

Connections with K-12 Content Area Frameworks: Asset-Based Stance

Through developmentally appropriate practice, educators gain a deeper understanding of commonality, individuality, and context of the children that they serve and adjust instruction to accommodate prior learning, cultural and linguistic differences, and differential experiences. In doing so, developmentally appropriate practice embodies an assets-based approach to instruction.

Methods that promote each child’s optimal development and learning through a strengths-based, play-based approaching to joyful, engaged learning. Educators implement developmentally appropriate practice by recognizing the multiple assets all young children bring to the early learning program as unique individuals and as members of families and communities. Building on each child’s strengths – and taking care not to harm any aspect of each child’s physical, cognitive, social, or emotional well-being – educators design and implement learning environments to help all children achieve their full potential across all domains of development across all content areas. DAP recognizes and supports each individual as a valued member of the learning community. As a result, to be developmentally appropriate, practices must also be culturally, linguistically, and ability appropriate for each child.

NAEYC, 2020 p.5

Developmentally appropriate practice requires early childhood educators to seek out and gain knowledge and understanding using three core considerations:

Current research and understandings of processes of child development and learning that apply to all children, including the understanding that all development and learning occur within specific social, cultural, linguistic, and historical contexts.

Example: Educators have a strong foundational understanding of the Rhode Island and Development Standards (RIELDS) and are also learners who consistently seek out research-based resources to improve their teaching and knowledge of child development and learning.

The characteristics and experiences unique to each child, within the context of their family and community, that have implications for how best to support their development and learning.

Example: Educators are cognizant of the unique characteristics of each child that they are supporting (e.g., identities, interests, strengths, abilities, languages, needs…etc.); educators engage with families in meaningful ways early and often.

Everything discernible about the social and cultural contexts for each child, each educator, and the program as a whole.

Example: Educators understand how different contexts within a child’s identity and life (e.g., race/ethnicity, language, gender, class, ability, family composition, socioeconomic status…etc.) intersect and impact their development and learning.

Through a deep understanding of the three considerations above, educators determine how curricula may be scaffolded and adapted to facilitate each child’s progress toward their individual learning goals. Developmentally appropriate practice involves flexibility in opportunities, materials, and teaching strategies offered to support each child’s individual learning needs.

DAP Teaching Strategies. NAEYC identifies 10 effective and Developmentally Appropriate teaching strategies. These teaching strategies cannot be achieved all at once; rather, an effective educator or family childcare provider is expected to remain flexible and observant, consider what children already know and are able to do and determine which teaching strategy is appropriate to use in a particular situation. The 10 DAP teaching strategies are defined below with respective examples:

Acknowledge

Acknowledge what children do or say. Let children know that we have noticed by giving positive attention, sometimes through comments, sometimes through just sitting nearby and observing.

Example: “Thanks for your help, Kavi.” “You found another way to show the number 5.”

Encourage

Encourage persistence and effort rather than just praising and evaluating what the child has done.

Example: [To an infant walking towards you]: “One more step – you’ve got this!”

“You’re thinking of lots of words to describe the dog in the story. Let’s keep going!”

Give Specific Feedback

Give Specific Feedback rather than general comments.

Example: “The beanbag didn’t get all the way to the hoop, James, so you might try throwing it harder”

Model

Model attitudes, ways of approaching problems, and behavior towards others, showing children rather than just telling them.

Example: To a toddler when another child wants his ball]: “There are more balls here, should we get him one?” [And walks over to get the ball for the other child]

Educator remarks, “Hmmm. that didn’t work and I need to think about why.”

Demonstrate

Demonstrate the correct way to do something. This usually involves a procedure that needs to be done in a certain way.

Example: Assist a toddler with handwashing, talking about it as you do it.

When following a recipe for making playdough, demonstrate how to measure out flour using a measuring cup so they can see what it looks like to measure a dry ingredient.

Create or Add Challenge

Create or Add Challenge so that a task goes a bit beyond what the children can already do.

Example: For infants, move a block that they are reaching for further away or bring it a little closer so they can successfully reach it.

For younger preschoolers, encourage children to move their arms and legs in a coordinated manner to “pump” on a swing, but stand nearby to offer support (via pushing) when necessary.

Ask Questions

Ask Questions that provoke children’s thinking.

Example: “If you couldn’t talk to your partner, how else could you let him know what to do?”

Give Assistance

Give Assistance (such as a cue or hint) to help children work on the edge of their current competence

Example: “Can you think of a word that rhymes with your name, Matt? How about bat… Matt/Bat? What else rhymes with Matt and Bat?

Provide Information

Provide Information, directly giving children facts, verbal labels, and other information.

Example: “This one that looks like a big mouse with a short tale is called a vole.”

Give Directions

Give Directions for children’s action or behavior

Example: “Touch each block only once as you count them.”

“You want to use the whisk to mix the flour and the water to create the dough.”

10 Effective DAP Teaching Strategies, National Association for the Education of Young Children: https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/topics/inforgraphic_DAP_2%202.pdf

To Learn More

Below are a variety of links to resources to learn more about Developmentally Appropriate Practice.

- Which DAP Resource is for Me? This webpage offers a wide range of resources on developmentally appropriate practice. Resources include content that supports NAEYC’s revised position statement and relates to equity and supporting children’s social and emotional development.

- DAP: Focus on Infants and Toddlers Online Module This online module available for purchase through NAEYC provides an overview of developmentally appropriate practice through narration, interactive knowledge checks, and sample classroom scenarios related to the 10 teaching strategies of DAP through an Infant/Toddler classroom lens.

- DAP: Focus on Preschoolers Online Module This online module available for purchase through NAEYC provides an overview of developmentally appropriate practice through narration, interactive knowledge checks, and sample classroom scenarios related to the 10 teaching strategies of DAP through a preschool classroom lens.

- Which DAP Resource Is for Me? This landing page offers educators a wide range of resources on DAP. These resources are organized by theme to support educators with finding a resource that best supports their needs.

Play in Early Childhood

Play is often talked about as if it were a relief from serious learning. But for children, play is serious learning. Play is really the work of childhood.

Fred Rogers

Play is essential to a child’s development. Researchers in the field of education, child psychology, and neurology have found play to contribute to the development of skills and behaviors across all core domains of child development written in the RIELDS: Physical Health and Motor, Social-Emotional, Language, Literacy, Cognitive, Mathematics, Science, Social Studies, and Creative Arts development. Neurologists who study the brain credit play with promoting early brain growth and development (NPR, 2014). As discussed in Section I and II of this Framework, play-based learning meets the needs of the whole child and supports the integrated nature of child development across various domains. In a single play experience, a child may develop physically as they engage in fine- and gross-motor activities and socially as they negotiate the play with peers.

Play is essential to a child’s development. Researchers in the field of education, child psychology, and neurology have found play to contribute to the development of skills and behaviors across all core domains of child development written in the RIELDS: Physical Health and Motor, Social-Emotional, Language, Literacy, Cognitive, Mathematics, Science, Social Studies, and Creative Arts development. Neurologists who study the brain credit play with promoting early brain growth and development (NPR, 2014). As discussed in Section I and II of this Framework, play-based learning meets the needs of the whole child and supports the integrated nature of child development across various domains. In a single play experience, a child may develop physically as they engage in fine- and gross-motor activities and socially as they negotiate the play with peers.

Connections with K-12 Content Area Frameworks: Student-Centered Engagement

Through student-centered engagement educators provide students with opportunities for individual and collaborative sense-making. When early childhood educators create intentional, play-based learning experiences, they provide children with opportunities to activate prior knowledge and expose them to academic concepts and social experiences in increasingly complex ways.

They use and learn language skills as they interact with their peers and cognitive skills as they plan, direct, and structure their play scenarios. Play also exposes children to basic concepts in science and social studies. For example, when an infant repeatedly experiments with dropping, throwing, or rolling a ball or other object they observe that the ball always falls to the ground at some point but that they can change how it moves and where it lands by how they act on it. They also learn about how their primary adults react and respond to their experiments with positive or negative feedback. In general, play supports a wide range of skillsets in four key areas identified as essential to life and work in the 21st century: critical-thinking and problem-solving, communication, collaboration, and creativity, also referred to as the “4Cs”. When educators intentionally design and plan learning experiences so they are rooted in play, children have opportunities to develop skills across the domains, generate knowledge of the larger world, acquire dispositions for learning that will last a lifetime.

Yet, while experts continue to expound a powerful argument for the importance of play in children’s lives, the actual time children spend playing continues to decrease. Today, children play eight hours less each week than their counterparts did two decades ago. Under pressure of rising academic standards, play is being replaced by test preparation in kindergarten and grade schools, and parents who aim to give their preschoolers a leg up are led to believe that flashcards and educational “toys” are the path to success. Our society has created a false dichotomy between play and learning” where none exists.

Fred Rogers

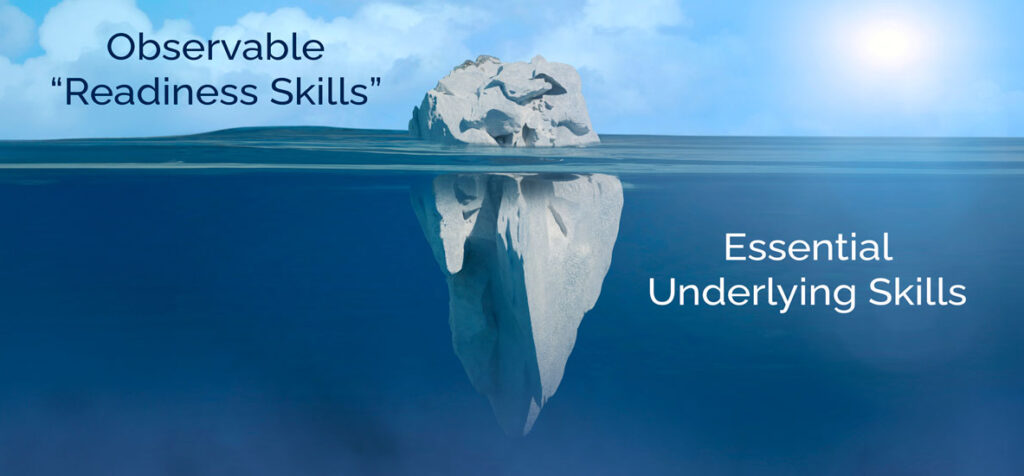

One reason for this dichotomy is that the benefits of play are not generally as directly observable as the school-readiness skills such as letter recognition, number skills, and letter/sound correspondence that are often taught through direct instruction. Although play can support these concrete skills, researchers more often associate play with benefitting the critical, but less directly observable skills that are foundational to school readiness. These include executive function skills such as working memory, flexible thinking, perspective taking, and self-regulation. When thinking about the benefits of play it is important to look “under the water” as well as above it, as indicated in the following graphic.

Working Memory

Flexible Thinking

Emotional regulation

Perspective taking

Letter recognition

Number skills

Letter/sound correspondence

Farran, D.S., 2022. Early Developmental Competencies: Or Why Pre-K Does Not Have Lasting Effects. Retrieved from https://dey.org/early-developmental-competencies-or-why-pre-k-does-not-have-lasting-effects/

Defining and Describing Play

Researchers have determined that play generally includes the following key elements: joy, active engagement, meaning or relevance, social interaction, imagination, and iteration and variety (Gray, 2017; Yogman et al., 2018; Zosh et al., 2018). Although active engagement is an essential element, an activity does not need to include all of these elements in order to be considered playful. Researchers categorize play in a few different ways, including by type of play (e.g., what children are playing with and how), by type of social play (e.g., how children interact with others during play, and by the continuum of play as it relates to how children and/or adults initiate and interact during play:

Types of Play

Although researchers express variations of how they categorize play, different types of play are generally described as physical play, language play, exploratory play, constructive play, fantasy play, and social play. Infants, toddlers, and preschool-aged children all engage in these different types of play, and all of these types of play are overlapping and incorporate benefits that are more of less directly observable.

Description

Crawling, rolling, climbing, running, jumping, chasing, wrestlingDeveloping large muscles and coordination

More directly observable benefits

- Developing large muscles and coordination

Less directly observable benefits

- Developing sense of self and confidence

- Learning one’s own physical abilities and limitations

- Developing impulse control

Description

Playing with sounds, making up words, singing to self, playing with rhymes, puns, and the rhythms of language

More directly observable benefits

- Developing phonological awareness

- Learning new words

- Developing pre-reading and writing skills

- Learning grammar rules

Less directly observable benefits

- Creativity with sound and language

- Thinking about meanings of words and similarities and differences

- Expanding communication skills

Description

Using all senses to observe objects, materials, and living things; acting on objects and living things to observe what happens; tinkering

More directly observable benefits

- Using tools for observations

- Learning about cause-and-effect relationships

Less directly observable benefits

- Curiosity and persistence,

- Motivation to explore and learn

- Risk-taking

- Critical thinking and problem-solving

Description

Building or making something using many different objects and materials including blocks, collage items, or recyclables.

More directly observable benefits

- Exercising motor skills

- Practicing hand-eye coordination

Less directly observable benefits

- Relationship between parts and whole

- Engineering design and innovation

- Critical thinking and problem-solving

Description

Take on pretend roles which may be roles in the family, community roles, fantasy characters, animals etc.

More directly observable benefits

- Exploring different roles and relationships

- Exercising the imagination

- Addressing fears or relieving stress

Less directly observable benefits

- Perspective-taking

- Problem-solving

- Creative and flexible thinking

- Communication

Description

Children engage in play with others

More directly observable benefits

- Taking turns

- Sharing

Less directly observable benefits

- Communicating with different children

- Cooperation and collaboration skills

Types of Social Play

Social play is especially important because it promotes basic social skills such as sharing and turn taking, as well as critical thinking (e.g., the ability to incorporate other perspectives into one’s own thinking) and the abilities to communicate and collaborate with others. It also supports speaking and listening skills (e.g., the ability to listen and respond respectfully to observations and ideas that differ from one’s own). The different types of social play described below are associated with certain ages and stages, however, keep in mind that children don’t simply move neatly from one type to the other nor should we expect them to. Rather, children develop skills in each stage while simultaneously strengthening their skills in the previous stages. The types of social play children engage in are also closely tied to their previous experiences with social play, the expectations around play in their families and cultures, their multilingual learner status, any developmental challenges they may have that impact communication and/or social interaction, and their individual temperaments (Rymanowicz, 2015):

Social play is especially important because it promotes basic social skills such as sharing and turn taking, as well as critical thinking (e.g., the ability to incorporate other perspectives into one’s own thinking) and the abilities to communicate and collaborate with others. It also supports speaking and listening skills (e.g., the ability to listen and respond respectfully to observations and ideas that differ from one’s own). The different types of social play described below are associated with certain ages and stages, however, keep in mind that children don’t simply move neatly from one type to the other nor should we expect them to. Rather, children develop skills in each stage while simultaneously strengthening their skills in the previous stages. The types of social play children engage in are also closely tied to their previous experiences with social play, the expectations around play in their families and cultures, their multilingual learner status, any developmental challenges they may have that impact communication and/or social interaction, and their individual temperaments (Rymanowicz, 2015):

This type of play is associated with infants exploring objects in their immediate vicinity. This type of play does not appear to have any organization but has many foundational benefits. It helps children gain knowledge of what their bodies can do and how they can move their arms, legs and other body parts and exposes children to resulting sounds, textures, and sensations they experience as they move. It also enables them to experience how their movements affect the immediate environment and how their actions cause different responses to the people around them. For older children, this type of play can fuel creativity and problem-solving as they try out what appears to be random strategies for exploring new objects and materials. Children engaged in unoccupied play benefit by having interactions with adults that draw their attention to the effects of their movements on their environment and the resulting stimuli they can observe through their senses.

Below are examples of children’s unoccupied play:

- An educator might say to an infant kicking a mobile: “Listen to the sound you made by kicking it with your feet! Ding! Ding! Ding!”

- An infant may reach for a dangling toy, splash their hands in water, or kick their feet.

- An infant may wave their hands and in the direction of a toy without further engagement with it.

This type of play is associated with older infants and young toddlers as they start moving away from a primary adult and reaching for, playing with, and interacting with objects independently. The ability to play independently is an important skill for children to develop and preschoolers will engage in this play, with some even preferring it. When a child engages in solitary play, they are generally deeply engaged in what they are doing and may not appear to notice what is going on around them. How children engage in this type of play is frequently connected to their previous experiences with play, the messages they get from their families about play, their temperaments, and/or their language knowledge. Educators can support this type of play by engaging directly with the solitary player and supporting their play by focusing on what they are doing, notifying, thinking, and wondering about. Learning more about their prior play experiences at home and their families (if they have siblings or friends they play with) can help the educator make decisions about when and how to support social play.

Below are examples of children’s solitary play:

- A toddler may use containers to fill and dump sand in the sandbox while not appearing to notice the activity happening in the playground.

- A preschooler may be so engrossed in painting a picture at the easel that they do not appear to notice children playing loud music with instruments in an adjacent area of the classroom.

This type of play involves children observing but not interacting with other children and is associated with toddlers but may occur at any time during the preschool years depending on children’s prior experiences, language, and temperaments. The onlooker child may ask questions of, or converse with peers, but typically keeps a distance and observes the play. This type of play enables children to learn through modeling and may benefit from the educator describing to the onlooker what the playing children are doing and/or supporting the onlooker to enter the play and help the play children invite the onlooker into.

Below are examples of children’s onlooker play:

- Children may observe how other children use the available materials, how they interact with one another, and the language and words they use as they play.

- A toddler or a multilingual learner may observe other children playing at the water table without making any moves to join in.

Children play alongside other children without any social interaction between them. Despite playing within proximity, children’s play does not typically overlap. This type of play benefits from individual interactions with the child who is parallel playing as well as support for them to begin and interact with children playing in proximity.

Below are examples of children’s parallel play:

- A toddler may play at the same water table with other toddlers, but not seem to notice what they are doing.

- A preschooler may build a structure with blocks while not engaging or even appearing to notice peers who are building collaboratively nearby.

This type of play is typically associated with young preschool-aged children and involves engaging with peers in a mutual activity or sharing toys and materials but not necessarily organizing their play in relation to one another. Children may engage in simple social interactions as they begin to practice social skills they have been introduced to through onlooker or parallel play. This type of play frequently involves support from the educator around sharing and turn-taking with materials.

Below are examples of children’s associative play:

- A child may share a favorite crayon with a peer at the art center or show a peer at the water table how they got water in a bucket.

- While at the sand table, children may talk with each other and share trucks and rocks; however, they are not playing with any formal plan or set of rules.

This type of play is associated with preschoolers and involves children organizing their play around shared goals and/or rules. This type of play frequently involves some controversy as children negotiate materials, roles, and what to do next. It requires frequent support from the educator to support sharing, turn-taking, and problem-solving.

Below are examples of children’s cooperative/collaborative play:

- Children may play “house” at the dramatic play area and agree on roles they will each play and begin to construct the play scenario together.

- While on the playground, children may organize a game with peers, such as tag or a relay race.

A Continuum of Play

Viewing play as a continuum is the most important way to categorize play, because it challenges the false dichotomy between play and learning and provides specific information for educators on how they can leverage play to support children’s development across the domains of the RIELDS. When adults think about play, they typically think about the two ends of this continuum, including “free” play that is child-initiated, child-directed, and child-structured OR play with games that is adult-initiated and structured including sports games, board games, and games such as Simon Says, or Head, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes.

According to play researchers, the most useful way to think about play in the classroom is to picture it on a continuum with free play at one end and games with other structured activities on the other end. In between these two endpoints is a broad range of child/adult interactions now referred to as “guided play.” Below is a chart that depicts the continuum of play-based learning, followed by descriptions that provide a more fulsome overview of each type of play (Pyle & Danniels, 2017). Although in this graphic the author uses the terms Inquiry Play, Collaborative Play, and Learning Play to describe different types of guided play as indicated earlier in this document, ALL types of play are important.

Research finds that the “quality of adult interactions in play scenarios may be more important than the quantity. When adults respond in a child-directed manner, children’s play can be more elaborate (White, 2012). Below is a more fulsome description of each type of play that falls on the continuum of play-based learning.

| CHILD DIRECTED |

EDUCATOR GUIDED | EDUCATOR DIRECTED |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free Play | Inquiry Play | Collaborative Play | Playful Learning | Games with other Structured Activities |

| Children initiate and direct their own play. Educators observe and facilitate the environment. | Children ask questions and explore ideas. Educators offer resources and nudge children to go deeper. | Educators co-design play with children and may join their play. | Educators set up experiences that children explore to meet specific learning objectives. | Children follow the rules of prescribed learning activities designed by educators to promote specific skills. |

| Running, jumping, make-believe, drawing, building with materials | Making instruments with elastic bands, investigating how worms move and simple machines work | Playing restaurant or grocery store with pretend money | Rehearsing and performing a scripted play, doing a scavenger hunt, baking cookies with a large, illustrated recipe poster | Matching and number line games, word bingo, rhyming word games, Simon Says, games using dice |

Adapted from Pyle & Danniels, 2017

Free Play. In free play, children have autonomy and control over what and how they play. During this type of play, children engage with different learning centers, materials, and peers based on their instincts, imagination, and spontaneous interests. Free play often takes the form of physically active play (typically outdoors), pretend play, socio-dramatic play, and constructive (building) play, or even creative arts. It rarely includes any specifically planned goals for children’s learning and development. It does, however, provide many opportunities for children to learn and practice new skills. During socio-dramatic play for example, children periodically step out of their pretend roles to make decisions about how the scenario will unfold or to assign roles to children who join in. The educator has a critical role in supporting free play and this includes intentionally planning for and supporting it. The following are some examples of how educators might support children’s self- initiated and self-directed play.

Examples of how you can support child directed free play

Free Play – Children initiate and direct their own play. Educators observe and facilitate the environment.

- Providing sufficient space and time for it in the daily schedule.

- Making open-ended objects and materials available that will stimulate children’s physical, dramatic, and creative free play with consideration to their ages and stages (e.g., balls of different sizes and shapes; dolls and dress-up clothes; paints, chalk, plain paper); and collections of natural materials, buttons, and other objects.

- Clearly labeling shelves with word and picture cues so all preschoolers, including multilingual learners, can select and replace them independently.

- Ensuring that spaces for free play are accessible to all children including those with physical disabilities.

- Giving specific praise for children’s free play such as I’m impressed by how you use your imagination to create that block building, or I enjoyed watching the family activities you created together in the dramatic play center.

- Modeling playful use of materials, for example using a leaf as a paint brush or using a toy block as a telephone

- Giving encouragement for children to solve problems that arise in their play rather than solving problems for children (e.g., how to get a block building to stand up or how to deal with disagreements about sharing materials or taking turns)

- Providing scaffolds for children who need emotional or language support to enter play. For example, you might help a child enter an existing play scenario “Juan would like to play. How can he join in?”

- Resisting the urge to engage in guided play when children are momentarily bored or unoccupied.

Guided Play. Guided Play combines child autonomy with adult guidance – children engage in child-directed aspects of free-play while adults provide scaffolding, for example, by setting up learning centers with intentional activities and materials related to learning goals, by organizing activities that encourage children to explore a particular concept, and/or by structuring activities to focus on specific skills (Hassinger-Das, Hirsch-Pasek, & Golinkoff, 2017; Weisberg et al., 2017). Educators then observe children’s play to formatively assess how they are using the materials and meeting broad learning goals. Below are three forms for support that Guided Play may take:

Inquiry Play. Adults prepare learning centers in the classroom with broad learning goals for supporting conceptual development and/or critical thinking and problem-solving, communication, collaboration, and/or creativity. They may provide objects, experiences, posters, and other materials to promote aspects of the curriculum, yet give the child autonomy to freely explore these materials on their own. Educators can support this type of play by:

Examples of how you can guide children’s inquiry play

Inquiry Play – Children ask questions and explore ideas. Educators offer resources and nudge children to go deeper.

- Setting up the dramatic play area to align with a thematic or topic focus (e.g., as a post office or supermarket for a community helpers or food unit)

- Providing materials for preschoolers to explore a concept such as shadows inside (e.g., flashlights, differently shaped objects, and a blank wall or surface) and outside (e.g., challenging them to change the sizes and shapes of their own shadows or to create shadow shapes with a partner)

- Providing materials for infants and toddlers that engage them in exploring size and shape (e.g., a variety of objects and containers with different-sized openings) or texture and how objects move (e.g., large balls and different surfaces to roll them on).

Providing “maker” materials for children to create their own tools for exploration, for example making their own instruments to explore sound (e.g., cups or boxes and thick rubber bands to make stringed instruments or containers made of different materials to make drums). - Supplying a variety of ways for children to meet goals for inquiry learning, for example, enabling children to meet goals for representation by talking about their process, showing it using paper or playdough, or demonstrating using props and their own bodies.

- Intentionally planning questions or challenges that will generate problems for children to solve. For example, what types of blocks work best for making tall towers? or What different colors can we make using primary colors, white, and black paint?

- Helping children share and compare their observations, experiences, and ideas before and after a playful exploration. How are our ideas the same and different?

- Supplying multiple cues for language in all phases of an inquiry-based activity including props, pictures, gestures, body language, and using cognates (words that sound the same in two languages such as insect/insecto or observe/observar).

Examples of how you can guide children’s collaborative play

Collaborative Play – Educators co-design play with children and may join their play.

- Supporting play “from the inside” by taking on a supporting role in children’s dramatic play (e.g., as a customer at the restaurant or a patient at the doctor’s office). It is important to note that educators should take on a supportive but non-dominant role (e.g., educator should be the patient at the hospital, but not the doctor).

- Interacting with children at play in ways that emphasize a specific concept (e.g., asking them about the sizes and shapes of blocks they used in their building play).

- Co-playing to support and build language development or exploration for example (e.g., playing alongside children at the water table and narrating their own observations and questions about how things sink and float).

- Supporting play “from the outside” by making suggestions for roles children might not have thought of to enrich the play scenario or guiding children to resolve disputes that arise in children’s group play to support social/emotional skills development.

Playful Learning. The educator sets up more structured experiences to address specific learning goals in a domain although cross-domain skills may be, and should be, integrated. Educators can support this type of play by:

Examples of how you can guide children’s play learning

Playful Learning – Educators set up experiences that children explore to meet specific learning objectives.

- Engaging children in a planting or playdough-making activity with sequenced steps to follow using word and picture cues to support specific communication (e.g., language, print concepts) and/or collaboration goals (e.g., sharing and turn-taking).

- Engaging children in group activities such as writing and illustrating a classroom book to support learning goals related communication (e.g., print or book knowledge and/or sound/letter correspondence) and/ or problem-solving and collaboration (e.g., what illustrations should be included and who will draw different ones).

Learning Games. Children also need opportunities to engage in structured play including games with rules. When designing these types of play opportunities, educators will determine specific goals and outcomes they want a child to achieve. Educators must individualize for children by using their knowledge of child growth and development and the RIELDS, to determine the appropriateness of a game based on children’s ages and stages and their family and cultural norms. Intentionality is key. This should be evident in the way the educator uses the curriculum and assessment data to plan and guide the play, how the educator engages children in and facilitates the play and how the play supports individual children’s progress toward the learning goals. Educators can support this type of play by:

Examples of how you can direct learning games

Learning Games – Children follow the rules of prescribed learning activities designed by educators to promote specific skills.

- Engaging children in games appropriate to their development levels. For example, older infants and toddlers will enjoy rolling a ball back and forth to you and or to you and one or two other children. For toddlers, you can gradually add simple rules like “roll the ball to the friend with a blue shirt on.”

- Providing age-appropriate board games for preschoolers such as Chutes and Ladders and/or Candyland. Remember that games with rules challenge children’s skills on several levels. Your goal may be for children to learn one-to-one correspondence as they move their game pieces, but they will also be practicing social skills such as turn-taking and executive function skills such as task persistence and impulse control.

- Adjusting the rules or shortening the game to address children’s developmental levels and prior experiences with structured games. For example, you might have a rule that players only go up ladders but not down chutes. If a child quits a game in frustration, then no learning has taken place.

- Creating your own board games to go with a topic or theme using poster board and markers.

- Incorporating movement and creativity into games while maintaining a specific learning objective. For example, children take turns rolling dice and choosing whether they want to jump, hop, or wave their arms to match the numeral rolled.

- Learning about games played in different families and cultures. For example, dominoes is a favorite game in some families that can be used to support matching and number skills at a variety of levels.

- Introducing toddlers to treasure hunt games to support early literacy development. For example, use large cards with word and picture cues of objects in the classroom for them to seek and find. You can increase the challenge as children get faster at finding the objects by including pictures of objects that are less easily observable.

- Engaging children in games such as Head, Shoulders, Knees and Toes to support goals for physical/motor development and coordination, language, and/or collaboration (moving in unison with others and the music).

- Facilitating large motor games such as Red Light/Green Light and Simon Says to support large and small muscle development, comprehension skills, and/or impulse control.

When educators have a comprehensive understanding of the intimate relationship between play and content learning, they can intentionally adjust their practices to support children’s play as well as their academic growth.

Bjorklund, Magnusson, & Palmer, 2018; Zosh et al., 2022

To Learn More

Below are a variety of links to resources to learn more about the importance of play.

- The Power of Play This white paper offers a unified definition of play, the ways in which early childhood development and play are intertwined, and tips for how educators can facilitate play within or outside of the classroom environment.

- The Importance of Play in Promoting Healthy Child Development and Maintaining Strong Parent-Child Bonds This clinical report highlights factors within the home environment that have reduced free play for young children and how advocates may support families, school systems, and communities with protecting play and maintaining a balance in children’s lives.

- The Power of Play: A Pediatric Role in Enhancing Development in Young Children This clinical report provides pediatric providers with the information they need to promote the benefits of play and to write a prescription for play at well visits to complement reach out and read.

- Play Research Kathryn Hirsh-Pasek, a Faculty Fellow in the Department of Psychology at Temple University and Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institute is dedicated to research examining the role of play in learning. Committed to translating current research in the science of learning for professional and lay audiences, this website provides the administrators, educators, and other ECCE stakeholders with digestible research on key topics related to play and other aspects of early learning.

- The Importance of Play for Young Children (Chapter 1 excerpt) This Chapter 1 excerpt from “This is Play” discusses play in the context of the Infant and Toddler years; specifically, what play looks like in the early years, why play is essential to growth and development, and how educators can best support play for the youngest age ranges.

- Active Play in Many Languages This article presents the benefits of active play as a way of promoting social connections for new multilingual learners in the classroom as well as some tips on preparing and communicating in ways that support safe and collaborative gross-motor play.

- Guided Play: Principles and Practices This article expands upon the ways that Guided Play techniques enhance curriculum and may lend itself as a successful approach for education across a range of content.

- Summertime, Playtime This article discusses the importance of free play in children’s lives within the context of the summertime and selecting a child’s summer programming.

Integrated Curriculum

Through use of the RIELDS and a RIDE-endorsed high-quality early childhood curriculum to fidelity, early childhood care and education partners will develop a greater understanding of the integrated nature of child development. To quote an excerpt from The Integrated Nature of Learning (2016), “Young children build knowledge as they make sense of their everyday experiences. However, they do not build domain-specific knowledge separate from knowledge in other domains. For example, they do not build concepts that are solely about mathematics in one moment and solely about language in another moment.” Breaking with conventions from K-12 education where children are exposed to content areas through specific learning blocks – such as a Literacy Block and a Mathematics Block, early childhood development occurs simultaneously through children’s engagement in routine activities, play, and the social environment.

Consider the following learning experiences in a preschool classroom

Imagine a classroom with large windows, of which a bird feeder is attached outside. Inside the classroom’s science/nature center nearby is a clipboard on a table that a child can use to record their observations of the birds that they see visiting the feeder. Printed on the paper attached to the clipboard are images and written names of different species of birds, and space for children to record observations. We may observe children counting the number of birds per species that visits the feeder (Counting and Classification, working memory), record a written or drawn observation of the characteristics of the birds they see (fine motor development, emergent writing, cycle of inquiry, visual arts), and share their observations with peers and familiar adults (expressive language, cycle of inquiry, relationships with others). Through this exemplar classroom activity, it is possible for a child to grow in areas of Physical Health & Motor, Social-Emotional, Language, Mathematics, Cognitive, Science, and Creative Arts development simultaneously.

The example above is just one small instance of how early learning is integrated across all areas of development, and while specific domains of learning are identified, each area of learning is influenced by progress in others. Recognition of cross-domain learning through is necessary when considering the entirety of the instructional cycle as integrated curriculum, instructional strategies, and assessment practices are interconnected. When we plan curriculum and anticipate the breadth of skills that a children may use in a particular activity, educators will be better equipped to use instructional strategies to support cross-domain learning and will be able to anticipate the areas of development to observe and record for assessment. An integrated approach to the instructional cycle will support the development of the “whole child.”

The “Get Ready: Prepare the Environment” subsection of this Framework provides detailed guidance on how educators may design their classroom and learning centers up for success, based on ITERS-3 and ECERS-3 quality metrics, and ways to integrate cross-domain learning within and across different learning centers. Furthermore, Section IV of this framework offers guidance on the integrated nature of child development and curriculum as it relates to assessment. Through responsive classroom design and teaching practices that support an integrated curriculum, educators will be able to strengthen the development of the whole child.

To Learn More

Below are a variety of links to resources to learn more about the importance of play.

- The Integrated Nature of Learning This publication examines how play, learning, and curriculum work together in early education. It describes the relationship context for early learning and the role of the educator in supporting children’s active engagement in learning. The discussions facilitated in this publication reveal the ways in which learning experiences in one domain are connected to learning in other domains.

- The Science and Mathematics of Building Structures This article is a case study of how a unit on buildings, supported by thoughtful educator preparation of the environment, supports children with experiencing integrated learning of science and math concepts within a language and literacy learning context.

- Cross-Domain Development of Early Academic and Cognitive Skills This opening paper presents the background to a Special Issue devoted to cross-domain development of academic and cognitive skills in young children (Birth – 8). The larger Special Issue contains 22 articles centered on core domains of school readiness and how these domains develop together and are affected by other factors and domains.

- The Building Blocks of High-Quality Early Childhood Education Programs This policy brief identifies important elements of high-quality early childhood education programs as indicated by research and professional standards, of which standards and curricula that address the “whole child” are critical.

Building Positive Relationships

No significant learning can occur without a significant relationship.

Dr. James P. Comer

Building relationships is an integral part of creating a safe and unified early learning classroom. Keeping in mind theories of attachment developed by John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth, attachment relationships in the earliest stages of life play an important role in a child’s development and their ability to create and maintain healthy relationships later in life. An attachment bond is developed with figures closest in one’s lives and in early childhood, this may include primary caregivers, siblings, close relatives, or educators. When children have a secure attachment with someone, they feel safe, seen and known, comforted, valued, and supported to explore. If trusted adults act in ways that are inconsistent, rejecting, or even neglectful, this secure attachment may be compromised, and children may develop insecure attachments in their social relationships, experiencing feelings of rejection, neglect, and fear. These insecure attachments impact the development of a variety of social-emotional skills – such as the development of self-help, self-regulation, confidence, and relational skills – and largely increases the risk for externalizing problems (Attachment Project, 2022; Pasco Fearon et al., 2010; Mayo Clinic, 2022).

Research finds that the emotional climate of a classroom characterized by an educator’s approving behavior, positive emotional tone, and active listening is associated with gains in children’s cognitive self-regulation skills (CSR). CSR skills assessed were related to sustained focus, working memory, attention shifting, and inhibitory control.

(Fuhs, Farran, & Nesbitt, 2013)

Positive and responsive educator-child relationships and interactions are an active and crucial ingredient for building a strong attachment bond and supporting children’s growth and development. Responsive caregiving refers to a caregiver’s nurturing and intentional interactions with a child based on their strengths, temperaments, areas for growth, and unique needs. For Infants and Toddlers, serve and return interactions (“give-and-take” interactions) between a child and responsive caregiver builds neural connections that strengths a child’s brain to support the development of communication and social skills. According to the Center on the Developing Child, when a baby babbles or uses facial gestures or expressions and adults respond with similar vocalizing and gestures, the interaction “creates a relationship in which the baby’s experiences are affirmed and new abilities are nurtured” (National Council on the Developing Child, 2004, p.2). Children’s early learning is social, and relationship based. When educators use responsive caregiving practices children are more confident, collaborative, and open to new learning (ELKC, 2020). Every moment represents an opportunity to support positive relationships. Establish them early and nurture them consistently to help children achieve positive outcomes.

Interactions are the words and gestures that you share with others. Within a single school day, a educator will have many different “everyday” interactions with children – often spontaneous, warm, caring, and encouraging. Whether it be a simple classroom welcome greeting, or a conversation in a learning center, everyday interactions between educators and children occur all day long and are important components to establishing a strong relationship between a educator and a child. When educators engage in interactions with children that are intentional, purposeful, and culturally responsive, however, these “everyday” interactions transform into “powerful interactions” and have the most significant and positive impact on a child’s learning. Through powerful interactions, educators develop a deeper connection with children – one of trust and security – and are more confident, focused, and open to learning. As researchers note, when an educator engages in a powerful interaction, they “make a conscious decision to say or do something that conveys to the child, “I notice you, I’m interested in you, and I want to know you better” (Dombro, Jablon, & Stetson, 2020).

There are three steps that an educator can pursue to turn an ordinary, everyday interaction into a powerful interaction:

- Tune into what is going on throughout the classroom.

- Reflect upon your feelings and emotions and how your beliefs, values, and biases may impact your interactions with each child.

- Plan what you would like to accomplish in the day – the goals for learning that you would like to see evidence of, and the strategies that you can use to expand this learning.

- Give your full attention to the child that you are interacting with and show interest in their activities.

- Take notice of the eye contact, level, and facial expressions that you are using in your interactions; ensure that your signals are warm, positive, and attentive.

- Use mirror talk to describe what a child is doing; reflect or repeat back what the child is saying or doing.

- Ask the child questions about their activity.

- Encourage the child to try something new or to think in new ways.

- Introduce new vocabulary and use modeling to strengthen language growth.

- Demonstrate new skills and scaffold/provide support during play.

- Tune into what is going on throughout the classroom.

- Reflect upon your feelings and emotions and how your beliefs, values, and biases may impact your interactions with each child.

- Plan what you would like to accomplish in the day – the goals for learning that you would like to see evidence of, and the strategies that you can use to expand this learning.

- Give your full attention to the child that you are interacting with and show interest in their activities.

- Take notice of the eye contact, level, and facial expressions that you are using in your interactions; ensure that your signals are warm, positive, and attentive.

- Use mirror talk to describe what a child is doing; reflect or repeat back what the child is saying or doing.

- Ask the child questions about their activity.

- Encourage the child to try something new or to think in new ways.

- Introduce new vocabulary and use modeling to strengthen language growth.

- Demonstrate new skills and scaffold/provide support during play.

The three steps outlined above should happen sequentially to support more powerful interactions with children. Through this process, educators will find that their interactions will be more intentional and individualized, partnerships with families with grow, and the classroom culture and climate will improve. An intentionally designed and implemented curriculum, classroom environment, thoughtful schedules, and educator reflection can also improve the quality of educator-child and child-child interactions, and are discussed in greater detail within this Framework.

Dombro, A.L., J. Jablon, & C. Stetson. 2020. Powerful Interactions: How to Connect with Children to Extend Their Learning. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

To Learn More

Below are a variety of links to resources to learn more about the importance of play.

- Attachment in Early Care and Education Programs This tip sheet provides strategies to promote responsive relationships and quality care with infants and toddlers.

- A Guide to Serve and Return: How Your Interaction with Children Can Build Brains In this guide, educators will learn more about what “serve and return” interactions are, the science behind it, and easily implementable strategies for engaging in these interactions with children.

- Responsive Caregiving as an Effective Practice to Support Children’s Social and Emotional Development This webinar, facilitated by BabyTalks, provides researched-based teaching strategies that support responsive caregiving and the importance of healthy, early relationships in a child’s life.

- Building Positive Relationships with Young Children (Supporting Social Emotional Development) In this video, educators, family child-care providers, and early childhood experts discuss the impact that adult relationships with children have on children’s development, behavior, and readiness to learn and share strategies for building these strong relationships with all children ages Birth through Five.

- Building Positive Relationships in the Early Childhood Classroom This article provides tips on how educators can build closeness with the children that they serve and how they can minimize conflict in their classroom.

- Advancing Equity in Early Childhood Education This position statement adopted by the NAEYC National Governing Board in 2019 is a foundational document that outlines steps needed to advance equity in early childhood education. This document provides specific recommendations to educators and program leaders for advancing equity and offers a synthesis of current early childhood education research through the lens of equity.

Universal Design for Learning

Universal Design is not a “special ed” thing, or even a “general ed” thing. It’s just an “ed thing.”

Mike Marotta

Every child has unique developmental and learning needs and, when setting up an early childhood classroom environment for success, educators must teach with an approach that accommodates the needs and abilities of all learners. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a framework that removes the physical and structural barriers within an environment to support access. In providing multiple and varied formats for instruction and learning, UDL ensures that all children have access to learning environments, a general education curriculum, and everyday routines and activities (NAEYC, 2009). Ultimately the goal of UDL aims to change the design of the environment rather than changing the learner. When a curriculum is easily accessible, all children are primed to become “expert learners” – a learner that is aware of their own learning needs and is able to seek out ways to ensure that those needs are met. By reducing environmental and structural barriers to learning, all learners will have the ability to engage in rigorous and meaningful learning.

The UDL guidelines developed by the Center for Applied Special Technologies (CAST) is a tool, offering educators concrete suggestions that can be applied to learning in any developmental domain to ensure that all learners can access and participate in meaningful, challenging learning opportunities. UDL guidelines are organized horizontally and vertically: vertically, the guidelines are organized according to three principles of UDL – engagement, representation, and action and expression. The guidelines are also organized horizontally by offering educators different strategies for supporting each of the three principles.

Listed below are descriptions of what each of the three UDL principles are and some examples of what this may look like in an early childhood classroom:

Multiple means of engagement

Learners differ in the ways that they are engaged or motivated to learn; this is influenced by a child’s neurology, culture, interests, and background knowledge along with a variety of other factors. No one means of engagement is a perfect fit for all learners in all contexts; therefore, providing options for engagement is essential.

Below is an example of how the matching of upper and lower-case letters is varied based on children’s interests:

- On the block rug, there are cars with lower case letters and garages with upper-case letters.

- In the water table, there are foam lower case letters and various containers labeled with upper case letters.

- Outdoors, there is a hopscotch set up with lower case letters and bean bags for tossing with upper case letters.

Multiple means of representation

Learners differ in the ways that they perceive and comprehend information that is presented to them. Some children may grasp information more efficiently through visual or auditory means while others may be more receptive to content through kinesthetic learning (learning while doing). There is no one mean of representation that will be of perfect fit for all learners in all contexts; therefore, providing options for representation is essential.

Below is an example of how the exploration of the concept of patterns may be universally designed:

- Books with pictures of patterns are available and read.

- Posters with patterns are displayed within appropriate centers at children’s height and are used in guided instruction.

- Using musical instruments to explore patterns of sound.

- Movement activities are presented at group or outdoors that involve patterned fingerplay or gross-motor sequences (e.g., hop, step, hop, step)

- Pointing out patterns in nature (e.g., the pattern of veins on leaves)

Multiple means of action and expression

Learners differ in the ways that they can navigate a learning environment and express what they know. Action and expression in learning require strategy, practice, and organization – all of which look different among different learners. Children with physical disabilities (e.g., cerebral palsy) will physically approach a learning task differently than a multilingual learner, for example. Likewise, a multilingual learner will express and communicate themselves differently than a child that has an executive function disorder. There is no one mean of action and expression that will be optimal for all learners; therefore, providing options for action and expression is essential. Below are examples of the varied ways that a child may express their knowledge of a story:

Below are examples of the varied ways that a child may express their knowledge of a story:

- Arranging felt pieces depicting the characters and scenes from a book in the correct sequence on a felt board.

- Drawing a picture of a scene from a story that was memorable to them.

- Acting out a story in the dramatic play center.

- Using puppets to retell a story.

To Learn More

Below are a variety of links to resources to learn more about utilizing universal design in your classroom:

- Universal Design for Learning Guidance version 2.2. This website provides a wealth of information related to the UDL Guidelines, including the three overarching guidelines of UDL, and various “Checkpoints” that fall within these principles. Each checkpoint includes strategies that educators can use as guidance when implementing a curriculum with UDL considerations. The Research page provides viewers with research evidence by UDL Guideline Checkpoint.

- U.S. Department of Education-Funded Centers that Support UDL This resource provides a list of U.S. Department of Education-funded centers that support Universal Design for Learning (UDL). Each center offers information, guidance, and/or resources related to UDL.

- Tool Kit on Universal Design for Learning (UDL) This toolkit offers a collection of resources on Universal Design for Learning that expands two of the substantive areas addressed in the initial release of the Tool Kit, including assessment and instructional practices.

- Universal Design for Learning (UDL): An Educator’s Guide This article dissects the Universal Design for Learning framework developed by CAST and backed by research and evidence-based educational practices and utilizes videos and examples of what UDL looks like in the classroom.

- Creating Inclusive Environments that Support All Children This webinar explores how to support educators in implementing effective, evidence-based teaching practices and creating inclusive environments where every child feels safe and has a sense of belonging.

Meaningful Family Engagement

Families play a key role in supporting children’s learning and development and are a child’s first and primary educator. As such, a high-quality early childhood program must meaningfully partner with families to effectively engage them in their child’s early learning and development. Family engagement is defined as the “collaborative and strengths-based process through which early childhood professionals, families, and children build positive and goal-oriented relationships.” (Head Start EKLC, 2022). Family engagement should not be mistaken for “Family Involvement,” which is when a school or program “leads with its mouth” by telling families how they can contribute to their child’s education. In contrast, family engagement is much more collaborative with a program or school “leading with its ears” – listening to family’s goals, ideas, and concerns as partners in children’s education (Ferlazzo & Hammond, 2009).

Children are at forefront of all meaningful family engagement practices and, keeping this in mind, programs communicate with and involve family members as partners in their child’s education and in program decisionmaking. Meaningful family engagement is not simply a one-time event; rather, it is an ongoing cycle where families and staff work together to promote equity, inclusivity, and cultural and linguistic responsiveness to improve overall program practice and quality.

Children are at forefront of all meaningful family engagement practices and, keeping this in mind, programs communicate with and involve family members as partners in their child’s education and in program decisionmaking. Meaningful family engagement is not simply a one-time event; rather, it is an ongoing cycle where families and staff work together to promote equity, inclusivity, and cultural and linguistic responsiveness to improve overall program practice and quality.

Children need positive interactions with family members and peers to develop self-confidence, a sense of security, and a love of learning. Decades of research has shown that meaningful family engagement is related to improved/increased:

✓ Student achievement

✓ Attendance and behavior

✓ Social emotional skills

✓ Graduation Rates

(The IRIS Center, 2008, 2020)

Engaging with families does not happen overnight and does not happen through any one strategy; rather, family engagement is unique, individualized, and multi-pronged. NAEYC, in partnership with Pre-K Now through the Engaging Diverse Families Project (EDF) conducted a review of empirical research on family engagement and identified several overarching themes for a programs’ successful family engagement practice. Below, are 6 principles for effective practice, a description of the practice, and some examples for how this practice may be implemented in a program and/or classroom (NAEYC, 2010):

Table: National Association for the Education of Young Children (2010): Principles of Effective Family Engagement. Retrieved from: https://www.naeyc.org/resources/topics/family-engagement/principles

To Learn More

Below are a variety of links to resources to learn more about meaningful family engagement.

- RI Early Learning and Development Standards: Fun Family Activities These activity cards give families information and enjoyable ways to support the development and learning of young children outside of a school-based environment. The activities are based on the RI Early Learning and Development Standards and are intended to help children develop skills that are important for future learning.

- Head Start Parent, Family, and Community Engagement Framework This framework provides programs with a research-based, organizational guide for implementing Head Start Performance Standards for parent, family, and community engagement.

- Family Engagement Plan Suggested Activities This guidance provides strategies and suggested activities for effective family engagement activities that programs, and public-school districts may use to reflect and develop their own unique events and practice.

- Family Engagement: Collaborating with Families of Students with Disabilities This module addresses the importance of engaging families of students with disabilities in their child’s education. This module highlights some of the key factors that affect these families and outlines some practical ways to build relationships and create opportunities for involvement.

- Strengthening Relationships with Families (On Demand) This online module available for purchase includes practical strategies and useful resources to strengthen relationships with families in an early childhood program. The online module is 1 hour of professional learning and the content is aligned with the 6 principles of family engagement identified by NAEYC and shared in this section.

- Families and Educators Together: Building Great Relationships that Support Young Children This book available for purchase offers strategies, resources, and examples from early childhood programs on ways to engage families in the early childhood community.