Section 3: Implementing High-Quality Instruction Get Ready: Prepare the Environment

Organizing and Designing the Physical Space

The preparation of a developmentally appropriate physical classroom space prior to the start of the school year is an exciting time for educators. This is an opportunity for educators to start from scratch – reflecting upon best practices and areas of improvement from the prior school year to assemble the pieces of the classroom puzzle into a cohesive space. Additionally, educators and administrators are provided more time to review the expectations for Space and Furnishings in the ITERS-3 and ECERS-3 to build a space that is of high-quality and most responsive to the needs of the children that it will support knowing that classroom set up may vary year to year based on the needs of the children enrolled in the group.

When beginning the process of classroom design and organization, it is important for educators and administrators to keep in mind key design considerations related to space and boundaries, proximity and distance, home and culture, flexibility and permanence, and engagement in Learning/Challenging behavior (National Center on Quality Teaching and Learning, 2012). These key considerations and recommendations for organizing the physical classroom space are explained below:

General Classroom Space

The classroom is a blank canvas for educators to design prior to the start of the school year. When considering a developmentally appropriate organization of the physical space, the classroom must be of ample size that allows for children and staff to circulate freely. Throughout the classroom, there should be an ample quantity of furniture for routine care, play, and learning, such as cubbies for storage of children’s possessions, child-sized chairs for children to eat or work at, shelves for the storage of materials without overcrowding. The space must allow for a variety of interest centers, space for meals and group times, and natural lighting to come in through windows or skylights. Interest centers are a clearly defined play area intended for a particular type of play, with materials that are organized by type and stored so that they are accessible. Furniture is provided if needed and an appropriate amount of space is provided for the type of play being encouraged by the materials and the number of children allowed to play in the center. For example, if the science learning center can accommodate 3 children at a time, it is expected that this center has enough seats at the respective table, room for movement, and accessible signage to indicate “3 children” as the capacity. Learning center capacity will fluctuate depending on the purpose of the center and the size of the space.

The classroom is a blank canvas for educators to design prior to the start of the school year. When considering a developmentally appropriate organization of the physical space, the classroom must be of ample size that allows for children and staff to circulate freely. Throughout the classroom, there should be an ample quantity of furniture for routine care, play, and learning, such as cubbies for storage of children’s possessions, child-sized chairs for children to eat or work at, shelves for the storage of materials without overcrowding. The space must allow for a variety of interest centers, space for meals and group times, and natural lighting to come in through windows or skylights. Interest centers are a clearly defined play area intended for a particular type of play, with materials that are organized by type and stored so that they are accessible. Furniture is provided if needed and an appropriate amount of space is provided for the type of play being encouraged by the materials and the number of children allowed to play in the center. For example, if the science learning center can accommodate 3 children at a time, it is expected that this center has enough seats at the respective table, room for movement, and accessible signage to indicate “3 children” as the capacity. Learning center capacity will fluctuate depending on the purpose of the center and the size of the space.

Additionally, classrooms should utilize furniture that is designed for a specific activity whenever possible (e.g., an easel for art, sand-water table, dramatic play housekeeping furniture). While a rug is not required for every learning center in the classroom, furnishings that provide a substantial amount of softness must be accessible, such as through a child-sized couch, several cushions or pillows, a beanbag, or a small mattress. Educators must consider children’s needs when designing the layout of the classroom; for example, structural adaptations, such as through the installation of ramps, handrails, wheelchair access, push plates instead of doorbells, and door handles instead of doorknobs are ways in which classrooms may be more readily accessible for all. Additionally, spatial considerations must be made to allow children and adults with wheelchairs, walkers, and other assistive equipment, can freely move around and access all areas of the learning environment. For children that are sensitive to loud sounds and bright lights, educators may need to find ways to minimize noise and to create a dimly lit space for them.

Accounting for Proximity and Distance

Proximity and distance refer to the placement of interest centers across the physical space. When designing a classroom, educators and administrators must consider the proximity of centers with lower activity levels (e.g., Cozy space, Library, Writing) to centers with high activity levels (e.g., Blocks, Dramatic Play, Music & Movement). Quieter centers should be physically placed further away from noisier centers; through this separation, children immersed in quiet activities are less distracted by their peers in noisy centers and likewise, those in noisy centers have more flexibility in their noise level and animation. Spaces such as the Math/Manipulative, Science, Art, and Sensory have a medium noise level and may be placed in between noisy and quiet interest centers to serve as a “buffer,” or transitory space. Educators must be careful not to arrange all interest centers against the wall around the perimeter of the classroom. Rather, interest centers should be intentionally scattered throughout the room to prevent long stretches of open space for children to use as places to run, which would pose as a safety hazard. Educators may creatively use rugs, shelving units, and other furniture used for specific activities to create boundaries to define learning centers and to break up open space. Learning centers must also have separate access points as to not disrupt play; for example, a child or adult should not have to walk through the Block center to reach the Science/Nature Center. Different interest centers will require a different amount of space. Some centers, such as a “cozy area” may be intended to be for one child while the block center may accommodate 4 children. Classroom design and size of center must offer sufficient space to accommodate the type of play require and the number of children who want to participate. The capacity of the spaces must be clearly marked with signage and pictures/words to communicate to adults and children the capacity. Additionally, the space should be arranged in in an obvious way so that it is easily implied the capacity for the center. If a space for privacy contains 2 child-sized beanbags, then the furniture would suggest the center cannot contain more than 2 children.

Educators should also consider the proximity of learning centers to facilities or materials needed to complete activities for the given area. Sensory and Art centers should be located closer to sinks for children’s easy access for handwashing. Cozy spaces should be in low-traffic areas to allow for uninterrupted alone time. Shelving units containing toys and activities for a particular center should be located within the interest center so that materials are easily accessible for children’s independent use.

All spaces in the classroom must be visible to adults. Likewise, adults must be visible to children to allow for supervision.

Learning Centers

As defined by the ECERS-3, an “Interest Center” is a clearly defined play area set-up for a particular kind of play – materials are organized by type and stored for children’s easy access and furniture is provided to support the use of these materials. When building a high-quality physical space, classrooms should create the following number of interest centers by age-group: 2 (Infant Play Areas), 3 (Toddlers/Twos), and 5 (Preschool/Pre-K), including a “Cozy Area” which is one of the required interest centers across all age groups. The type and quantity of learning centers within a classroom is largely dependent on classroom size, layout, and educator preference; however, the ITERS-3 and ECERS-3 suggest that classrooms may consider the following (note: expectations for each learning center listed will vary by infant/toddler, or preschool/pre-k age grouping): Blocks, Art, Dramatic Play, Science/Nature, Math/Number, Fine Motor, Gross Motor, Music and Movement, Sand/Water, Space for Privacy/Cozy Area, and opportunities for engagement with language and books integrated throughout (Harms, Clifford, & Cryer, 2014; Harms et al., 2017).

Connections with K-12 Content Area Frameworks: Clear Learning Goals

By establishing clear learning goals, educators routinely use a variety of strategies to ensure that students are understanding what they are learning, why they are learning, and how they will know when they have learned it. When early childhood educators build learning centers with connection to a curriculum and observe and interact with children as they play in these learning centers, they will develop a greater understanding of whether the learning centers and instructional interactions are supporting children with achieving that learning goal.

Although each interest center includes a basic set-up and materials designed to support a particular type of play or activity, remember that children will deepen their understanding of concepts and develop their skills across the domains in every interest center. Also, an interest center, no matter how well-provisioned it is, cannot maximize children’s learning in a domain. For example, as children play in the block center, they are introduced to science and math concepts as they experience the properties and attributes of the building materials (e.g., size, shape, weight, and texture) and how these characteristics influence the designs they can create with different blocks. These are important standards-based concepts that are not available for children to fully explore in the math or science interest areas alone; rather, it is the integrated nature of early childhood curriculum that makes this type of learning and development possible. For each of the interest centers described below, you will find suggestions for creating cross-domain learning opportunities within and among the different centers.

Although each interest center includes a basic set-up and materials designed to support a particular type of play or activity, remember that children will deepen their understanding of concepts and develop their skills across the domains in every interest center. Also, an interest center, no matter how well-provisioned it is, cannot maximize children’s learning in a domain. For example, as children play in the block center, they are introduced to science and math concepts as they experience the properties and attributes of the building materials (e.g., size, shape, weight, and texture) and how these characteristics influence the designs they can create with different blocks. These are important standards-based concepts that are not available for children to fully explore in the math or science interest areas alone; rather, it is the integrated nature of early childhood curriculum that makes this type of learning and development possible. For each of the interest centers described below, you will find suggestions for creating cross-domain learning opportunities within and among the different centers.

Blocks

Blocks may take a variety of forms. When building the block interest center in in a classroom servicing Infants, toddlers, and twos, the center should contain soft blocks, cardboard blocks, and smaller blocks (e.g., alphabet blocks, table blocks) (Harms et al., 2017). In a Preschool/Pre-K classroom, the block center should contain unit blocks and, in the higher levels of quality, large hollow blocks (Harms, Clifford, & Cryer, 2017). Unit blocks are typically made of wood, plastic, or hard foam and are built on the same basic standard of measurement. Large hollow blocks, in contrast allow children to build larger structures and can be made of wood, cardboard, or plastic. Additionally, the block center may offer children “Accessories” that can be used with the blocks. These accessories may include small people, vehicles, animals, road signs, trees, or any other small figure that can enhance block play. The Block interest center is required in a classroom serving older Toddlers and Twos; however, classrooms with children aged 24 months and older must offer children access to block accessories to achieve a higher level of quality.

A Block center should be large enough for at least 3 children to build and contain ample storage on open shelves that are labeled with pictures and written language. A low pile rug or foam mat is recommended for this area to provide some level of softness and muffle any sounds from tumbling blocks.

To support children’s integrated learning, educators may:

- Provide clipboards, paper and pencils for drawing and writing about structures.

- Include dramatic play props such as builders’ hats and vests.

- Include books such as Dreaming Up and How a House is Built to inspire children’s building.

- Provide tools for measuring the size of their created structures, such as a tape measure, ruler, or yard stick.

- Display photos of children building and their structures.

- Display posters of buildings in the children’s community to inspire design and construction.

- Introduce challenges such as “Which blocks work best for making a tower/a school?” or “Choose an animal and design a home for it.”

Gross-Motor

A gross motor space are outdoor spaces that are spacious enough to allow for vigorous play, including running and the use of wheeled toys. Only when weather does not permit the use of outdoor space can an indoor space be substituted. Gross-motor spaces are easily accessible to the children and if not located within or adjacent to the classroom, do not require a long walk, disruption of other classrooms, or use of stairs to access. The spaces should be generally safe with no major hazards (e.g., protrusions are masked, protective cushioning for hard fall zones, bollards to protect a playground, (a short post used to create a protective or architectural perimeter), and may have two different play surfaces (e.g., one soft and one hard) to accommodate different types of activities.

Gross-motor spaces should contain enough stationery and portable equipment to interest all of the children and keep them active and involved. Stationary equipment may include climbing structures, ramps for crawling, cushions or rugs for tumbling, tunnels, basketball hoops, balance beams. Portable gross motor equipment may include wheeled toys, push toys, jump ropes, balls, and hula hoop. All equipment should be appropriate for the age and ability of the children that it is intended to serve. Through this equipment, children should be able to participate in a variety of age-appropriate skills such as reaching, crawling, swinging, jumping, hopping, tossing, catching, throwing, kicking, hanging by arms (for 4+ year olds only), pushing or pulling, or using a jump rope or hula hoop. The Public Playground Safety Handbook provides specifications for guidelines on safe playgrounds.

To support children’s integrated learning, educators may:

- Take advantage of any available outdoor natural spaces, the trees and other plants that grow there, and the small animals that live or visit there to enrich living-things-related activities.

- Provide tools for digging and for observing and collecting natural materials outdoors.

- Introduce gross motor art and music activities outdoors, for example, painting murals with water on the side of the school building or creating a marching band. - Note: Credit for instruments and art materials outside are only given after they meet the minimum requirement for gross motor time of 15 minutes for the ECERS-3 observation.

- Provide materials for explorations that require a lot of space, for example, balls and ramps or shadow activities.

Dramatic Play

Children frequently play pretend in all interest centers; however, the Dramatic Play center is a separate defined space where children clearly engage in pretend or make-believe play. In an Infant, Toddler and Twos classroom, the Dramatic Play center should contain many and varied materials that allow meaningful play. For Infant classrooms, the center may contain soft dolls, animals, pots and pans, toy food, toy telephones, toy vehicles, hats, and purses for dress-up, and small people and/or animal figures. For Toddler and Twos classrooms, the center may contain simple dress-up clothes, child-sized house furniture, cooking/eating equipment, dolls, doll furnishings, soft animals, play buildings with accessories, toy telephones, small people and animal figures, toy vehicles. The materials provided should promote the combining of props. If a toy pot is provided, for example there should be a spoon for stirring, or if there is toy food, there should be a method of collecting the food (shopping cart or basket). For toddlers and twos, the classroom should provide opportunity for children to engage in Dramatic Play not only within the indoor learning center, but also in the outdoor or indoor gross-motor space (Harms et al., 2017).

General housekeeping materials are a requirement within Dramatic Play centers. Other themes may be added into this center to support meaningful play with many and varied materials. In a Preschool/Pre-K classroom, the Dramatic Play center may a variety of materials that allow for engagement in a variety of play themes including (Harms, Clifford, & Cryer, 2014):

| Dramatic Play Theme | Examples |

| Family life at home | Home furnishings such as stove, sink, refrigerator, small table and chairs, and crib; household props such as dishes, utensils, play food, pots, baby dolls) |

| Different kinds of work | Doctor’s office; grocery store; hair salon; post office |

| Fantasy | Science fiction (e.g., time travelling, exploration); medieval castle; magician |

| Leisure | Camping; sports; birdwatching; beachgoing |

All Dramatic Play centers, regardless of age, should have materials that integrate at least 4 representations of diversity and the entirety of the dramatic play center should present a unified play theme. Representations of diversity may include, but are not limited to, representations of different races and ethnicities through dolls, foods of different families and cultures, and equipment used by those that are differently abled. This learning center should also contain furniture in accordance with the theme, such as a chair, tables, and child-sized kitchenette for home living, or a grocery market, and other props that enhance the theme of the dramatic play space.

To support children’s integrated learning, educators may:

- Create literacy opportunities by suggesting a library, post office, or bookstore play theme (make a field trip with children to get ideas for setting it up).

- Include props with authentic print such as calendars, cookbooks, address books, baby books in the languages spoken by children’s families (family life at home) or, for example, relevant signage, order forms, sales slips, or play prescriptions for different work settings.

- Introduce play themes for jobs or careers in engineering or science that are engaging but may be unfamiliar to children such as an architect’s office, a park ranger station, or a weather station.

- Provide materials and facilitate discussions related to mathematics explorations, when relevant to the theme of the dramatic play center. For example, if the center theme is a flower shop, provide cash register, money, and a telephone to increase exposure to written numbers and mathematic learning in daily events.

Art

The art center typically consists of a child-sized table that can accommodate 3-4 children, and an easel (if available) located within proximity to a sink. In addition to always carrying paper, the art center should contain at least one drawing material and a variety of age-appropriate art materials. An art center is not a requirement within an Infant classroom. For Toddler, and twos classrooms, the art center may contain crayons, watercolor markers, brush and finger paints, play dough, and collage materials of different textures (Harms et al., 2017).

Within a preschool/pre-K classroom, the art center should contain a variety of materials for child use from each of the following categories:

| Materials Category | Examples |

| Drawing materials | Crayons; markers; colored pencils; chalk; pastels |

| Paints | Tempera; watercolors; finger paint |

| Three-dimensional objects | Play dough; wood scraps; clay; cardboard boxes |

| Collage materials | Cloth scraps; yarn; paper scraps; foam shapes |

| Tools | Scissors; paintbrushes; stamps with pads; rulers; glue |

To support children’s integrated learning, educators may:

- Include displays on the wall or in binders of artwork done in various media.

- Rotate images and childhood stories of interesting artists and their work.

- Provide props for observational drawing (e.g., colored pencils for drawing the life cycle of a butterfly in the Science/Nature center).

Math

A math center contains materials that children can play with to learn math concepts and practice math skills. Infants, toddlers, and twos are capable of learning math and number concepts very early in life and as such, classrooms should contain many appropriate materials. For infant classrooms, math materials may include number picture books, grasping toys or rattles of different shapes, busy boxes with numbers or shapes, nesting cups, or stacking rings. Toddler classrooms may contain similar types of materials as the Infant classroom, in addition to some more complex materials – such as cash registers, toy telephones with numbers of keys, number blocks, and easy shape sorters, for example. Two-year-old classrooms may include pegs with number boards, blocks with various shapes and sizes, simple number puzzles, and safe tape measures. Aside from offering math materials in a defined learning center, educators may embed learning of math concepts in daily routines (e.g., giving a time warning before transition), and during music & movement activities (e.g., songs with counting or numbers woven into the lyrics) (Harms et al., 2017).

In a preschool/pre-k classroom, a classroom should offer at least 10 different appropriate math materials, with 3 materials belonging to each of the 3 categories of materials such as (Harms, Clifford, & Cryer, 2014):

| Materials Category | Examples |

| Counting/comparing quantities | Unifix cubes with number trays; small objects to count into numbered containers; games that require children to determine more or less; chart and graph activities for children to use by placing materials into cells; dominoes; playing cards; games with dice; abacus; pegboards with numbers printed and holes to match; puzzles where written numbers are matches to quantities on a puzzle piece; beads with bead patterns |

| Measuring/comparing sizes and parts of wholes | Measuring cups and spoons; a balance scale with things to weigh; items to measure (rulers, yardsticks, tape measures); height charts; puzzles with geometric shapes that may be put together; shape with parts to divide and put back together to make whole (fractions) |

| Familiarity with shapes | Shape sorters; puzzles with different geometric shapes; unit blocks with image/outline labels on shelves; geoboards; magnetic shapes (magnatiles); shape stencils; attribute blocks of different sizes |

The capacity of the math center will vary based on classroom space, furniture (tables/chairs) and shelving available. Math materials are to be used on tabletops and stored on open shelves for accessibility.

To support children’s integrated learning, educators may:

- Incorporate math concepts and skills into play in other interest areas. For example, introduce children to attributes of blocks during block-building activities and have them measure and compare the heights and widths of their structures; have them explore volume with different shapes and sizes of containers at the water table; have them categorize the books in the library by topic or organize the paint brushes in the art area by size.

- Introduce topics of study that engage children in using mathematics for data collection and analysis. For example, do an extended study of balls and ramps and have children collect data on how far different balls roll off a ramp. Combine their data on a class chart and have children share their ideas about what features of a ball make it a good roller and why they think so.

- Do a study of water and create a Venn diagram for categorizing items that float, sink, or stay suspended in water. Use the diagram to compare characteristics of these different objects and share ideas about characteristics that matter in sinking and floating.

- Guide children to collect natural materials while outside and compare and contrast the characteristics of the materials (e.g., collecting fallen leaves or rocks and organizing the materials by size, shape, and color).

Science/Nature

Infants, toddlers, and twos, children may interact with nature through the exploration of natural things outdoors (e.g., infant sitting on blanket on grass; toddlers exploring dandelions in the yard) or by being provided experiences with nature indoors (e.g., watching birds at the birdfeeder while indoors, pointing out plants in the classroom). Educators may augment children’s interactions with the natural world through appropriate books, pictures, or toys that represent nature realistically. Having a defined Science/Nature or a Sand/Water table are not required in an infant or toddler classroom; it is recommended for classrooms serving twos (Harms et al., 2017).

A preschool/pre-k classroom should have a defined Science/Nature center that contains at least 15 nature/science materials belonging to 5 categories, listed below:

| Materials Category | Examples |

| Living Things | House plants, class pets, outside garden |

| Natural Objects | Rocks, seashells, bird’s nest, pinecones, insects in transparent plastic |

| Factual books/nature-science picture games | Matching Game (adult animals with their babies); book about different kinds of sea life |

| Tools | Scale, magnifying class, microscope, magnets |

| Sand or water with toys | Sensory table with digging tools, measuring cups, containers |

The center should contain at least 5 books related to nature/science. While artificial representations of natural objects (e.g., cloth flowers, plastic insects) may be placed within this learning center, these objects are not counted as a “nature/science material” defined by the ECERS-3 (Harms, Clifford, & Cryer, 2017).

Science is an active process of inquiry and children need authentic, facilitated opportunities to use and engage with the practices of science during active and on-going investigations in Physical, Life, and Earth/Space science. Care should be taken to ensure that the science area is maintained as a vibrant and engaging space and that the science children experience is enhanced by, but not limited to the science area.

To support children’s integrated learning, educators may:

- Rotate materials in the area so that they align with a current topic or reflect a concept or phenomenon children have expressed an interest in. For example, you might include rocks children collected outdoors along with a container with separate compartments for organizing the rocks in different ways.

- Ensure that materials in the science area are conceptually related and not a random collection. For example, along with plants you might include a watering can, a spray bottle, measuring tools, a field guide or children’s book about plants, and a notebook to collect and record information about their growth over time. Along with a basket of shells, you might include a field guide to shells and photos showing where different shells are found in nature.

- Guide children to collect natural materials while outside and compare and contrast the characteristics of the materials (e.g., collecting fallen leaves or rocks and organizing the materials by size, shape, and color).

Reading

Exposure to and interactions with books is critical to help strengthen infant, toddler, and twos’ emerging language and literacy development. While classrooms serving children under the age of three are not required to have a clearly defined reading center, it is expected that books are accessible to children throughout the classroom. The ITERS-3 recommends the classroom offer at least 10 books to children; however, the more books available, the better. Books for this age group are expected to be reachable, and have easily turned pages, clear pictures, and length and number of printed words to match children’s developmental ability. Electronic books (e-books) are allowable if they are accessible for children’s independent use, and any sound or animation is turned off (Harms et al., 2017).

Within a preschool/pre-k classroom, books are organized in a defined reading interest center, including several comfortable furnishings accompanied by some other softness. The reading center may consist of rugs, child-sized furniture, book storage (bookshelves, open shelves, baskets) and pillows, bean bags, or large soft toys (e.g., stuffed animals) that children can lean on. The reading center should contain many books – defined as at least 20 books for 10 children, 30 books for 15 children, and 1 more for each additional child (Harms, Clifford, & Cryer, 2014).

Books are expected to be easily reachable, in good repair, developmentally appropriate for the ages and interests of the children, and absent from frightening, violent, or negative content. A wide selection of books covering a variety of general topics should be included, such as variations in gender, race, cultures, feelings, occupations, health, sports/hobbies, abilities, among others.

To support children’s integrated learning, educators may:

- Include nonfiction books on topics of interest such as children’s field guides (e.g., to trees, birds, insects) and other books with interesting and detailed images children can describe and talk about (even if the text is advanced).

- Incorporate wordless books and books written in the primary home languages of children in the class; look for children’s book readings on YouTube done by native speakers.

- If possible, provide multiple copies of a popular or topic-specific book so children can “read along” with each other while each holding their own book.

- Display photos of a variety of people reading alone and together or even photos of children’s families reading together at home.

- If space allows, include a rocker or adult sized chair that invites an adult and child to read together.

Cozy Area and Space for Privacy

A cozy area is a clearly defined space with a substantial amount of softness where a child may lounge, daydream, read, or play quietly and escape the normal hardness of the typical early childhood classroom (e.g., wood or tiled floors). The space may be furnished with a soft rug, pillows, cushions, beanbags, and other items that add to its softness. The cozy area should be placed in an area of the classroom that is protected from interruption, actively play, and is used for calm/quiet activities.

A space for privacy is an area that gives children relief from the pressures of group life. The space from privacy is a smaller space where 1 or 2 children can play. The signage, size of, and furniture provided within this space should obviously way to signal the capacity of the space for no more than 2 children. This space is to be placed in a quieter location in the room where it is protected from intrusion and distraction. Children using the space should be allowed to move materials with them to the space, if their preference is to work alone (e.g., child wants to take a toy truck with them from the block center to the private space). A space for privacy may be used for any type of play if it is limited to 2 children and is protected from active play and interruption. Some common spaces for privacy include an art easel, writing center, sand/water table, or lofted nook (Harms, Clifford, & Cryer, 2014).

When arranging the classroom space, it is important to keep in mind that a cozy area is not recommended for infant or toddler classrooms (it is recommended for Twos), however these spaces need more soft furnishings accessible to create a warm and comfortable classroom environment for these youngest learners. A cozy area and space for privacy are both required in a Preschool and Pre-K classroom. These spaces may be the same area if they are protected from interruption, active play, and are used for calm and quiet activities.

To support children’s integrated learning, educators may:

- Include books centered on identifying and expressing feelings and/or bedtime type stories with simple, predictable text such as Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown.

- Display a feeling poster and/or children’s drawings of themselves expressing different emotions.

- Provide soft toys (stuffed animals).

- Provide sensory fidget toys such as sensory bottles, stress balls, sensory tubes, and pop bubble toys.

Music & Movement

Activities related to music and movement may be confined to a specific learning center in a classroom; however, this is not necessarily a requirement. Rather, music and movement activities should be accessible for child engagement throughout free/choice play. Some educators may choose to define a music and movement center and store materials there. Others may choose to embed these toys within other centers, such as in a gross motor center. Music and movement may include access to musical instruments, recorded music, singing, or other movement activities.

Educators may engage infants and toddlers with music and movement related activities by offering them musical materials (e.g., rattles, blocks with bells in them, push toys that pop), singing songs and lullabies, playing age-appropriate song recordings, and/or by leading children in movement activities (e.g., finger plays, dance). Offering age-appropriate musical instruments (e.g., drums, xylophone, cymbals) are only expected for twos, preschool, and pre-k classrooms (Harms et al., 2017). Within the preschool/pre-k classroom specifically, opportunities to engage in music and movement should be plentiful, including access to at least 10 different musical instruments, and access to other group singing/dancing activities, should be accessible for at least 1 hour (Harms, Clifford, & Cryer, 2014).

When designing the classroom environment educators should be wary of the types of instruments available, the location of the music/movement activities, the time of day that this play is offered, and the overall noise level that these activities may create.

To support children’s integrated learning, educators may:

- Take instruments into the gross motor space indoors or outdoors where children can play loud music, dance, sing, and march. - Note: Credit for instruments and art materials outside are only given after they meet the minimum requirement for gross motor time of 15 minutes for the ECERS-3 observation.

- Play different types and genres of music to create a mood in an interest center or to accompany a learning activity.

Fine Motor/Manipulatives

The fine motor/manipulative center, like music & movement, may consist of activities embedded within other learning centers (e.g., math and art), or may be a separate space entirely if classroom size allows. Fine motor materials should be age-appropriate and accessible to children throughout a bulk of fine and free play time blocks. For infants, fine motor materials may include grasping toys, busy boxes, nested cups, textured toys, cradle gyms, and containers to fill and dump. For toddlers and twos, these materials may include shape sorting games, large stringing beads, large peg boards with pegs, simple puzzles, and medium or large interlocking blocks (Harms et al., 2017).

In the preschool/pre-k classroom, this center should contain materials from 4 distinct categories and note that at least 1 material from each of these categories should be accessible to children throughout the classroom (Harms, Clifford, & Cryer, 2014):

| Materials Category | Examples |

| Interlocking building materials | Interlocking blocks of varied sizes |

| Art materials | Crayons or pencils for writing; scissors for cutting; playdough and tools for rolling/squeezing/cutting |

| Manipulatives | Stringing beads; pegs and pegboards; table blocks |

| Puzzles | Floor puzzles, framed puzzles |

To support children’s integrated learning, educators may:

- Make use of manipulative toys as nonstandard measuring tools, for example, have children use pegs or unifix cubes to measure their and their classmates’ heights or the sizes of their block structures.

- Use manipulatives in counting, sorting, sequencing, and categorizing activities.

- Use puzzle activities as an opportunity to support problemsolving and teach children how to look for clues to determine whether a given piece fits in a particular space.

All learning centers should be clearly marked with signs that include a picture of the learning center, a written name of the center, and the number of children each center can have at capacity. Signage of the learning center as well as labels of stored materials accessible to children should be written in the languages of the children in the classroom.

Creating a Child-Centered Space

A high-quality early learning classroom supports all children, inclusive of race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, gender, age, home language, or ability level. The classroom is intended to be an extension of a child’s home environment where they can feel loved, supported, and reflected. As such, the physical environment of the classroom should be designed in a way where children feel they have “ownership” over their environment.

When building the classroom, educators may first reflect upon the ways that they can make the space feel “home-like.” Previously discussed under “Learning Centers,” some centers should contain more or less furnishings that offer a degree of “softness.” Soft furnishings allow children to escape from the normal hardness of the typical early childhood classroom and provide the classroom with more of a home-like feel. Classrooms should also be designed to accommodate displays that are easily visible to children. Displays may contain children’s individualized work (artwork that a child carries out in their own creative way), photographs (of children with peers or family), and other materials related to a curricular theme, topic, or current interest. The more materials on display that relate directly to the work children have completed, their interests, and their community, the more they will feel like the physical space is an environment that the environment belongs to them and they belong in the environment.

When building the classroom, educators may first reflect upon the ways that they can make the space feel “home-like.” Previously discussed under “Learning Centers,” some centers should contain more or less furnishings that offer a degree of “softness.” Soft furnishings allow children to escape from the normal hardness of the typical early childhood classroom and provide the classroom with more of a home-like feel. Classrooms should also be designed to accommodate displays that are easily visible to children. Displays may contain children’s individualized work (artwork that a child carries out in their own creative way), photographs (of children with peers or family), and other materials related to a curricular theme, topic, or current interest. The more materials on display that relate directly to the work children have completed, their interests, and their community, the more they will feel like the physical space is an environment that the environment belongs to them and they belong in the environment.

Educators should also reflect upon the ways that the physical space promotes inclusion. In reference to the ITERS-3 and ECERS-3, a high-quality classroom contains at least 10 easily visible positive examples of diversity among books, displayed pictures, and accessible play materials.

Below are a few of the ways that diversity may be integrated into the classroom:

- Play food within the dramatic play center contain a variety of diverse food options pizza (Italian), tacos (Mexican), Sushi (Japanese), or croissants (French) to represent diversity.

- Books within the reading center contain representations of children with varying races, genders, abilities, interests, or languages.

- Singalong songs featuring a variety of languages - signing language for some words or playing songs from different cultures.

- Posters hung around the room may show adults with non-traditional gender roles (e.g., show women and men as firefighters).

- Shelves, center signs, and other child-focused texts are accessible in children’s home languages in addition to English.

Balancing Consistency and Flexibility

An educator will need to negotiate between maintaining consistency and allowing for flexibility in their classroom as they become more familiar with individual needs of the children that they serve. Children crave consistency – a topic discussed in greater detail under “Schedules & Routines.” There are elements within an early childhood classroom setting that provide a framework for consistency throughout a school year – including the types of learning centers offered, the components and basic structure of the daily schedule, and the classroom routines. The consistency in these overarching systems make children feel safe, secure, and comforted in an environment where they have greater control over knowing what to expect. Therefore, it is critical to maintain consistency wherever it makes sense to throughout the school year to provide children with this comfort.

Research shows that changes in the classroom environmental arrangement, such as the rearrangement of furniture, implementation of activity schedules, and altering ways of providing instructions around routines have been found to increase the probability of appropriate behaviors and effectively decrease the probability of challenging behaviors.

An early childhood classroom, however, is also an ever-evolving environment that requires observing, reflecting, and modifying to best accommodate the needs of children. As the year progresses, educators must be flexible in reorganizing certain classroom elements based on changes in needs. Despite thoughtful planning, there are elements of the design of the classroom that may not always work, and educators must be flexible in adapting the environment to children’s needs. At the beginning of the school year, educators will be able to see how children interact with the classroom layout and may need to rearrange the space to be more supportive if it is serving as a barrier to productive learning. Educators will have to continuously question whether the organization of the space prevents runways and large open spaces, minimizes disruption between centers, is safe and allows for educator monitoring, and is child centered. Spaces that are not organized in a way that works need to be reconfigured to meet children’s needs.

Many of RI’s Endorsed List of Preschool/Pre-K Curricula are organized into units of study, with weeks dedicated to the exploration of a particular topic/theme. Throughout the school year, educators will need to be mindful to adapt learning centers to align with curricular themes, children’s interests, and additional opportunities for topical expansion and exploration. Educators may consider the types of materials that are accessible within the centers, rotating materials to allow for a mix of familiar and new, refreshing displays with new materials based on topics explored and children’s interests, and adapting the environment and materials for children’s use. By having aspects of flexibility and change in the classroom, educators will keep their classroom a fresh and exciting place to learn in; however, maintaining in schedules, routines, general classroom arrangement, and other classroom expectations, provide children with a sense of safety and comfort.

To Learn More

Below is a variety of links to resources to learn more about organizing and designing the physical classroom space.

- Early Childhood Environments: Designing Effective Classrooms This online, self-paced module guides learners through the elements that make up a well-designed early childhood environment and the strategies that educators may user to make the classroom environment more conducive to children’s learning and development. Perspectives and resources are provided on the physical, social and temporal early childhood environment.

- Designing Environments This video and supporting resources provide educators with a variety of guidance, resources, and activities to support the features of the physical and social classroom environment that maximize young children’s engagement and learning.

- Resources for Infant/Toddler Learning Environments This list provides a variety of resources to guide educators in thinking about setting up an Infant/Toddler learning environment up for success. The resources will guide thinking about play spaces, areas for caregiving routines, and ways to integrate home languages into children’s environments.

- Developing a Deeper Understanding of All Young Children’s Behavior This article discusses how culture shapes our views, values, beliefs, and even our expectations for children’s behavior and provides educators with actionable strategies to reflect upon instructional practices to support cultural diversity in the classroom.

- Calendar Time for Young Children: Good Intentions Gone Awry This article provides a fresh perspective on the use of “calendar time” in the classroom based on child development and best practices.

- Studies vs. Themes: 5 Ways They Differ This article describes some essential differences between curricular “themes” and “studies.”

Creating Meaningful Classroom Routines and Schedules

Schedules and routines are key components of creating a classroom environment that is responsive, engaging, and intentional. While these terms are often used interchangeably, they each have very different meanings (Head Start ECLKC, 2022):

- Represents the "big picture;" the main activity blocks that happen throughout the day

- E.g., Small group time, Outdoor/Gross Motor time, Morning Meeting

- The steps needed to complete each part of the schedule

- E.g., Washing hands after playing outside; clean up toys before transitioning; helping educator set the table for snack on Thursdays

- Represents the "big picture;" the main activity blocks that happen throughout the day

- E.g., Small group time, Outdoor/Gross Motor time, Morning Meeting

- The steps needed to complete each part of the schedule

- E.g., Washing hands after playing outside; clean up toys before transitioning; helping educator set the table for snack on Thursdays

Schedules and routines influence children’s emotional, cognitive, and social development; they provide children with a sense of safety, security, and comfort in providing a sequence of activities that are to be expected from day to day. In turn, children gain a greater sense of control and autonomy over their environment and community over the predictability of their daily lives and their ability to be active participants in their education and care setting.

While more formulaic schedules are normative for preschool-aged children, it is important to note that schedules must be more fluid within an Infant and Toddler classroom. Infant and Toddler schedules should promote individualized care and adapt to each child’s interests, needs, and abilities to support their development (State Capacity Building Center, 2020). If an Infant is tired and needs to sleep, for example, the schedule should be flexible and responsive to the child’s need for a nap. That said, infants and toddlers still benefit from a schedule and routines that establish a sense of regularity in their day. When experiencing familiar activities and routines on a daily basis, infants and toddlers develop relationships with people they interact with and gain a sense of belonging and self-confidence and will grow to develop a greater independence and adaptability (Hemmeter, Ostrosky, & Fox, 2006). As children grow and develop, a class wide schedule and accompanying routines will be more developmentally appropriate.

Schedules

Schedules represent the “big picture” of the main activity blocks that occur within a given day. In the classroom environment, schedules assist educators with organizing the day into concrete units of time and arrange meaningful experiences for children. Schedules typically include time for free play, small group learning, snacks/meals, gross motor/outdoor play, transitions, read-alouds and more. The Rhode Island Department of Education, in recognition of best practices for early childhood education structure, recommend that programs offer a full, 6-hour day (360 minute) schedule, 5-days a week. A full-day schedule offers children more opportunity to engage in high-quality learning activities throughout the day and enables educators to implement a chosen curriculum with greater fidelity. Research finds that full-day programs have substantial, positive impacts on child development including, but not limited to, cognition, literacy, math, social-emotional, and physical development (REL, 2021). Regardless of whether a community-based Organization or Local Education Agency can offer a full- or partial-day of early childhood programming, when creating a daily classroom schedule, there are a variety of key considerations that educators must factor in:

Connections with K-12 Content Area Frameworks: Formative Assessment

Formative Assessment is used in the K-12 space as a method of analyzing teaching and student learning and is identified as one of the core high-quality instructional practices. To be discussed in greater detail in Section IV of this framework, formative assessment is a critical type of assessment that is routinely used in the early learning context.

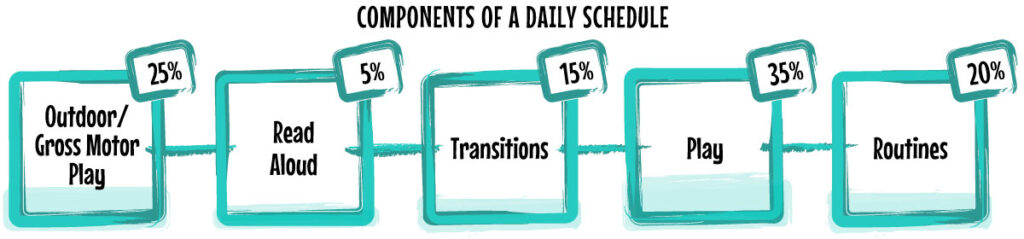

RIDE considers a full day to consist of a 6-hour day; however, recognizes that programs may operate on a longer or shorter schedule. Regardless of duration, RIDE recommends prioritizing play and gross-motor opportunities while also allotting time for necessary routines, transitions, and read aloud opportunities. As indicated above, it is strongly encouraged that book reading is not exclusively delivered in a whole group format; rather, it should be embedded throughout all learning centers where appropriate. Below is an exemplar breakdown of key components in the daily schedule. The graphic on this page provides an overall breakdown of key components within the daily schedule and approximately how much time each activity should consume in an average day for classrooms operating on a full, 360-minute (6-hour) schedule. The schedule will vary by program duration and should be adjusted as necessary, in recognition that more or less time will be spent on activities based on the length of the day.

Routines

Routines consist of the small, multi-step activities needed to accomplish components of the daily schedule. Routines are regularly occurring activities and procedures typically found within the arrival, bathroom, clean-up, snack/meal, story, nap, and departure times of the day. A series of responses to a clean-up routine, transitioning from choice time to read-aloud may involve:

Teaching Schedules & Routines

Once schedules and routines are established, educators need to plan the ways in which they will communicate it to the children in their classroom.

Infant/Toddler Considerations:

Within an Infant and Toddler classroom, the placement of the schedule is primarily intended for use by families and teachers. Schedules for Infants and Toddlers should be individualized based on a child’s individual needs in the moment (e.g., feeding a hungry baby; putting a child down for a nap when they are tired; changing a dirty diaper when necessary. As children get older, a more general routine will be followed. It is recommended that programs develop strong relationships with families to gain a greater understanding of the child’s schedule.

When teaching the daily schedule, educators should be mindful to:

- Post the schedule in place(s) that are noticeable and accessible to children throughout the day.

- Follow the schedule consistently to set a precedent for predictability in the classroom.

- Individualize instruction of the schedule for children so that all children can develop an understanding of these shared expectations. Educators may use a combination of auditory (e.g., clapping, timer, music) and visual (e.g., pictures, photos, graphics, words) to signal the sequence of scheduled activities within a day. Educators should explain the schedule using home languages wherever possible – learning basic words of phrases and including home language on a written classroom schedule.

- Provide positive and constructive feedback on children’s efforts to follow the schedule.

When teaching routines, educators should be mindful to:

- Model expected behaviors within a given routine for children. If a child is having difficulty cleaning up a learning center, for example, the educator should sit with the child and guide them with the steps of the cleaning up process (e.g., If a child spills sand from the sand table onto the floor, the educator may suggest the child may grab the dustpan and brush to clean it up). As with daily schedules, educators may integrate a child’s home language into instruction of the routines either verbally (if they can speak the home language), or by learning basic words/phrases and written language.

- Maintain a schedule of predicable classroom routines throughout the school year. It is important to note that predictable classroom routines benefit all children, especially multilingual learners by allowing them to anticipate what will happen each day, including the type of language they will need for each activity (Bunce & Watkins, 1995; Tabors, 2008)

- Use visual supports to assist children with following the steps within a routine independently (e.g., next to the sinks in the bathroom, an educator may display a sequence of images outlining the handwashing process)

- Offer positive and constructive feedback on children’s efforts to follow routines.

To Learn More

Below is a variety of links to resources to learn more about creating meaningful classrooms routines and schedules.

- Calendar Time for Young Children: Good Intentions Gone Awry This article provides a fresh perspective on the use of “calendar time” in the classroom based on child development and best practices.

- Daily Routines and Classroom Transitions This landing page provides a variety of resources that support daily routines and transitions in the classroom.

- Helping Children Understand Routines and Classroom Schedules This training kit provides important content to assist in-service and pre-service providers conduct staff professional development activities on understanding routines and classroom schedules.

- Schedules and Routines This video shows how schedules and routines help to promote children’s learning. This video is part of a series of 15-minute in-service suites on Engaging Interactions and Environments

- Classroom Transitions This video provides educators with strategies for helping children to use positive behaviors during classroom transitions.

- Individualized Care This resource communicates the importance of individualized care. It promotes essential program practices to ensure quality in family childcare and center-based programs that serve infants and toddlers.